#47 Ujjal’s odyssey

Journey After Midnight: India, Canada and the Road Beyond

by Ujjal Dosanjh

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2016

$34.95 / 9781927958568

Reviewed by Hugh Johnston

First published November 21, 2016

*

Journey After Midnight is Ujjal Dosanjh’s memoir of his journey from a village in the Punjab to London in 1964, and to Vancouver in 1968. His extraordinary journey would see him become the 33rd premier of British Columbia and a federal cabinet minister. Hugh Johnston reviews the life and 20-year political career of India’s best-known immigrant to BC — Ed.

*

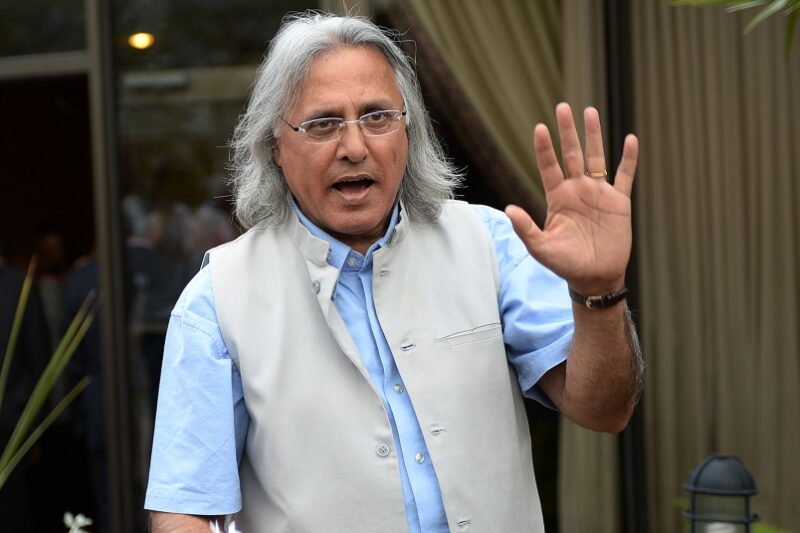

Ujjal Dosanjh was the just the second provincial premier of non-European descent ever to hold office in Canada. The first was Prince Edward Island’s Joe Ghiz, whose father was a Lebanese immigrant. Dosanjh, in contrast, is an immigrant himself. He made the leap from new arrival to government leader within his own lifetime.

Ujjal Dosanjh was the just the second provincial premier of non-European descent ever to hold office in Canada. The first was Prince Edward Island’s Joe Ghiz, whose father was a Lebanese immigrant. Dosanjh, in contrast, is an immigrant himself. He made the leap from new arrival to government leader within his own lifetime.

While he was premier of British Columbia, Ujjal Dosanjh visited his homeland of India at the invitation of the Indian and the Punjab governments. This happened during the Christmas break of 2000-01, when Dosanjh had time for a fast tour of northern India. It was a most exceptional experience for a returning emigrant to receive all the publicity, fanfare, formal hospitality, and elaborate security of a guest of the Indian state.

He met officially and socially with India’s leading national politicians and with their counterparts in several Indian States, and with other national celebrities and luminaries. Understandably, he spent as much time as he could in his home state of Punjab where he made a point of visiting his birthplace village of Dosanjh, which carries the name of his ancestral family.

It says something about the warmth of his reception in India that the Government of Punjab paved a broken, pothole-filled lane of half a kilometre from the main road into the village of Dosanjh, just so he could drive there, rather than walk in or be flown by helicopter. His family village was the beneficiary of this new blacktop road built for his visit — not just because he was a Punjabi emigrant who had made good, but because he was one who had impressively risen to high political office in a “white man’s country.”

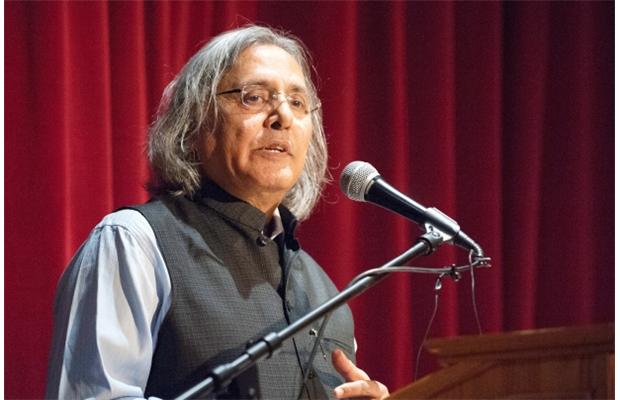

His account of the challenging and unpredictable rise of that career makes for compelling and enlightening reading. And he tells the story superbly in English, a language that he ultimately mastered as an adult. He also tells it with disarming honesty and modesty.

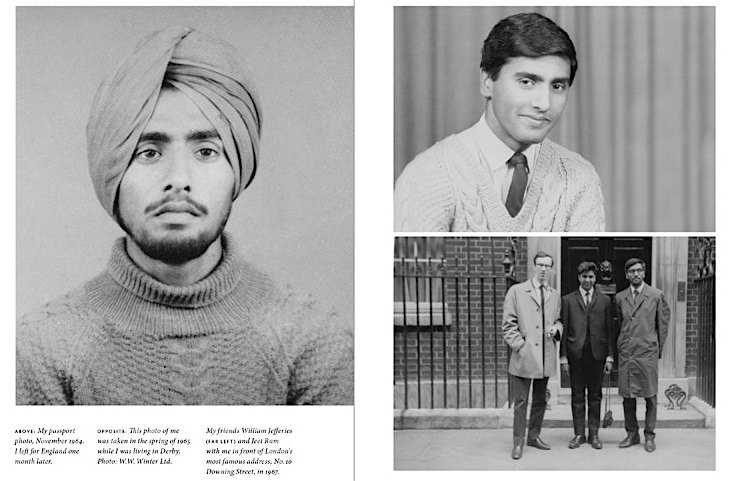

Dosanjh’s book is an autobiography to be appreciated for the author’s exemplary independence, courage, and principles. He left India at the age of eighteen, encouraged by the example of another student from his local secondary school. His declared purpose in his visa application was to enroll in an electrical engineering college in London.

In retrospect, Dosanjh concedes that he was basically an economic emigrant, like many others, attracted mainly by the affluence of the West. He did come from one of the leading families in his small farming village and he had an admirable father who valued education; but, by western standards, his family lived in poverty. His father was an experienced man — educated beyond secondary school — a former contractor and a teacher and the founder of the village primary school. But his father did not have the means to pay for a university education overseas for an adult son.

What got Dosanjh to Britain was a one-way airfare to London, paid for by his father who obtained the money from a maternal aunt. Dosanjh stepped bravely off his plane in London’s Heathrow airport in 1964 with very little money of his own, entirely dependent on the natural generosity of relatives and fellow villagers who had settled in Britain ahead of him. They gave him initial shelter and helped him find work, as other Punjab immigrants were also doing for countrymen and kinsmen.

Dosanjh’s experience was like that of many from India and Pakistan who found that Britain offered them industrial work and little else. He describes a succession of low-level jobs: in a railway yard, in a crayon factory, and as a lab assistant running a projector. None of these jobs enabled him to pay tuition fees, let alone take any time off work for a college education.

After three and a half years he re-migrated to British Columbia. In Vancouver he had an aunt and uncle who sponsored him as a landed immigrant and found him work in a sawmill. In Vancouver he could earn enough to combine work and study. Within eight years of his arrival in 1968, he had completed a BA, graduated from law school, and been called to the bar, all while marrying and starting a family.

Dosanjh was an activist from the moment he landed in Canada. His time in Britain had been a preparation for this, and his incessant reading a stimulus. He puts his command of English when he first landed in London at a rudimentary grade four level. But he quickly became a news junkie and an enthusiastic user of local public lending libraries.

His political outlook was shaped in the West of the 1960s — by the examples of Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Pierre Trudeau. But he had also grown up with family members in Punjab who had a powerful commitment to progressive and revolutionary ideals: his maternal grandfather had been prominent in the anti-British movement before Indian independence and had served time in jail as a political prisoner.

In Vancouver, Dosanjh quickly found companionship and purpose among left-leaning opinion-makers and organizers. These were people he met through his family, or more generally within the South Asian community, or at Langara College and at SFU. In this company, he educated himself on contemporary questions of race, gender, gay rights, and liberal values. One gathers that this was a growing experience for him that reinforced his natural inclination towards independent thought, making him suspicious of extremists and increasingly committed to Gandhi’s way and non-violence.

His early Canadian experience also reinforced his inherently secular worldview. The narrow religious nationalism that he encountered within his own Sikh community was something he quickly rejected. And he applauded the opposition to French Canadian nationalism that defined Pierre Trudeau’s politics of those years. Dosanjh came to see the growing religious-ethnic nationalism of his own Sikh community and the provincial nationalism of French Canadians as comparable and similarly negative forces.

Dosanjh writes about what drove him to speak out fearlessly against extremism within his own community. He spoke his mind when the silence of the majority and the violent threats of a minority would have dictated abundant caution. He reminds us of the appalling troubles of Punjab and the Punjabi diaspora in the 1980s and 1990s, when nearly the whole Punjabi community in Canada was intimidated by the presence of terrorists in their midst. These years witnessed a growing list of terrible acts related to the Sikh community — bombings, shootings, and beatings.

Dosanjh and his wife Rami had been booked to fly to Delhi on Air India’s tragic flight 182 in June 1985. This was the flight carrying 329 passengers and crew that was blown up over the Atlantic by a bomb that terrorists had placed on board in Vancouver. Ujjal and Rami Dosanjh fortunately had cancelled their booking a few days before.

A few months earlier, Dosanjh had been assaulted by a turbaned Sikh wielding an iron bar who inflicted deep wounds to his head requiring 84 stitches to repair. This attack happened at the end of a working day in a darkening parking lot and ended only when Dosanjh’s law partner arrived on the scene, scaring the attacker off and saving Dosanjh’s life.

For some time before that, Dossanjh had been receiving threats to his life and to the life of his family. And the threats continued afterwards. But Dosanjh says that his near death experience in that parking lot attack gave him a renewed sense of life’s purpose. It did not stop him from playing a public role and speaking the truth.

All the foregoing helps explain the direction of Dosanjh’s political career from his beginnings in Canada. He was a lumber union organizer, an advocate for Punjabi farm workers, and an NDP party worker almost from the start, taking up issues that mattered most to Punjabis in B.C. while simultaneously acquiring an understanding of and commitment to issues of broadly Canadian concern.

At the summit of his career he was still dismissed by some opponents as an “ethnic” candidate, although his success at election time and his handling of issues in government belied the charge. He makes it clear that the Sikh and South Asian community was the base that launched him into politics, but when in 1991 he was first elected as an MLA — after two unsuccessful tries — it was in a riding that was fifty percent Chinese and that had a large general Canadian population, and that was only five percent Sikh and South Asian.

For a candidate like himself, the greatest challenge was to capture a party nomination. For that purpose, party membership drives were a necessity that Dosanjh understood and pursued, but which he says he never enjoyed or felt comfortable about.

He also insists that the outrage expressed by outsiders about membership drives in the Sikh community was one-sided. He has learned enough about Canada’s electoral past to know that other ethnic communities had long been the targets of mass membership drives by all political parties. The drive for a party nomination frequently put Sikh politicians — including Dosanjh — into bitter competition with each other.

There was also a “double whammy,” he says, in being identified too closely with an ethnic group. Contenders ran up against an unofficial party practice of limiting the number of candidates from a single ethnic group, and they encountered the fear from within the group that one person’s success would ruin another’s chances. Dosanjh tells enough to give a good understanding of the hazards faced by a so-called “ethnic” politician.

Dosanjh deserves great credit for the principled role he played in the provincial and federal governments between 1991 and 2011 as an NDP member of the legislature, caucus leader, cabinet member, premier of British Columbia, Liberal Member of Parliament, and federal minister of health. He made difficult decisions in major portfolios and gained general respect in the process.

As a young man, Ujjal Dosanjh had unrealized ambitions as a writer in Punjabi, and it is not surprising that he writes with sensitivity and telling effect here. He records the best and worst of his political career frankly and convincingly. In doing so, he gives us insight into an unprecedented life in politics, and he describes a contemporary life that wraps Indian, Canadian, and global citizenship into a single frame.

*

Hugh Johnston is a professor emeritus in history at Simon Fraser University, where he has taught for many years. His publications include The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada’s Colour Bar (revised edition 2014); The Four Quarters of the Night: the Life Story of an Emigrant Sikh (with Tara Singh Bains, 1995); and Jewels of the Qila: The Remarkable Story of an Indo-Canadian Family (2011).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster