#35 Canada’s forgotten superstar

Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the World’s Youngest Explorer

Fredericton, New Brunswick: Goose Lane Editions, 2016

by Christian Fink-Jensen and Randolph Eustace-Walden

$24.95 / 9780864928955

Reviewed by Bonnie Reilly Schmidt

First published October 31, 2016

*

Recently BC’s remarkable Aloha Wanderwell (born Idris Hall, 1906-1996) was recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the first woman to drive around the world. Here’s a link to the Wikipedia entry; and here’s what Carrie Rickey of the New York Times had to say about the book (April 22, 2019):

She clocked 380,000 miles in the 1920s, traversing six continents, often in places where paved roads were unknown. Newspapers called her the ‘Amelia Earhart of the open road.’ She radiated star quality onscreen and electrified lecture audiences with her tales of the road.

Here, for the Ormsby Review, Bonnie Reilly Schmidt reviews the first biography of Wanderwell, penned by Christian Fink-Jensen of Victoria and and Randolph Eustace-Walden of Vancouver — Ed.

*

A book about the world travels of a small band of adventure-seekers in the 1920s may seem archaic in a day when space tourism is fast becoming a reality. But, as the authors of Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the World’s Youngest Explorer know only too well, it is the irrepressible human spirit in adventurers, and not always a particular destination, that resonates for readers across time. This is especially true of a young Canadian woman with the unlikely name of Aloha Wanderwell.

A book about the world travels of a small band of adventure-seekers in the 1920s may seem archaic in a day when space tourism is fast becoming a reality. But, as the authors of Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the World’s Youngest Explorer know only too well, it is the irrepressible human spirit in adventurers, and not always a particular destination, that resonates for readers across time. This is especially true of a young Canadian woman with the unlikely name of Aloha Wanderwell.

Aloha began her life as Idris Hall in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1906, and she grew up in North Vancouver, Qualicum Beach, and Victoria. Idris’s Canadian beginnings, however, do not feature prominently in her life story largely because she only returned to the country of her birth a handful of times after moving to Europe in 1919, usually to see her sister Miki, who lived near Courtenay. It was while at Nice in the south of France that fifteen-year-old Idris answered an ad placed in a Paris newspaper by Walter Wanderwell seeking “Brains, Beauty — and Breeches: World Tour Offer for a Lucky Young Woman.” It was only after Walter agreed to become Idris’s legal guardian and provide a return ticket home if she wanted one, did her mother agree to let Idris join the expedition.

It is not surprising that Captain Wanderwell’s exciting offer appealed to a young girl searching for adventure. Walter was a larger-than-life character whose life (and unsolved murder) almost overshadows Aloha’s in the book. He was a complex, charismatic man who was part guru and sometimes tyrant to his band of intrepid explorers. He was a master of spin and spectacle who understood how to manipulate an audience, attract sponsors, and seduce young girls. Walter also harboured a secret past that included a wife in Florida and time in jail in the United States as a suspected German spy.

But Walter also had a creative side. He relentlessly promoted his idea for an international police force designed to control militarism and promote peace. He also capitalized on the new medium of film to record his record-setting adventures. Walter was ahead of his time when it came to modifying the Model “T” Ford vehicles he used for his endurance contests, making them lighter by substituting aluminum for their heavy metal frames. In 1932, he received a patent for his idea for an aftermarket Speed Slope for cars that made them more aerodynamic, an idea that Cadillac adopted for some of its models two years later.

After joining the expedition in 1922, Aloha soon became one of its key attractions. At seventeen, she became the first woman to drive a car across India. In 1928, she became the first to circle the globe by automobile, a feat that predated Amelia Earhart’s 1932 solo flight across the Atlantic and sealed her reputation as a female explorer.

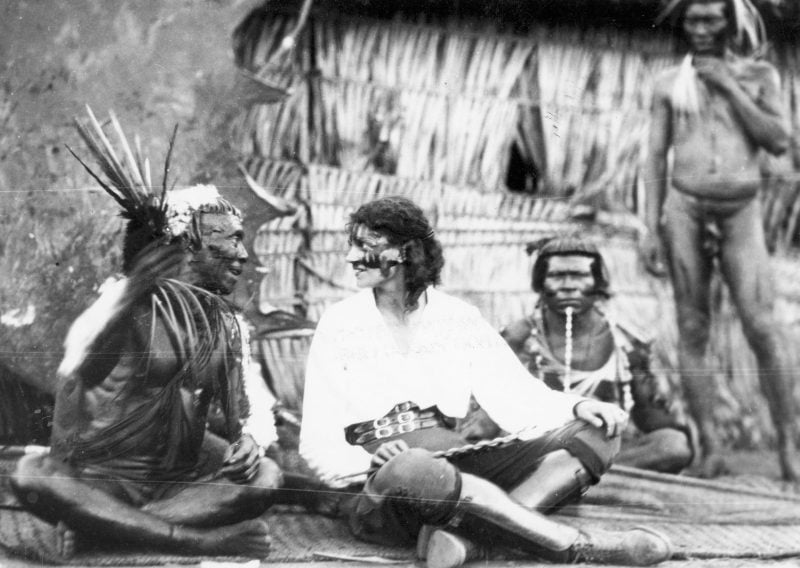

There was more to Aloha, however, than her travels. She soon became an accomplished cinematographer. Her film footage of the expeditions and her editing capabilities secured her the respect of Hollywood’s movie elite. Today, her 1930 footage of the previously-unknown Bororo tribe in the Brazilian rainforest is considered a significant anthropological achievement. Film historians are only now acknowledging Aloha’s cinematic contributions, which are housed in the Library of Congress, the Motion Picture Academy, and the Smithsonian.

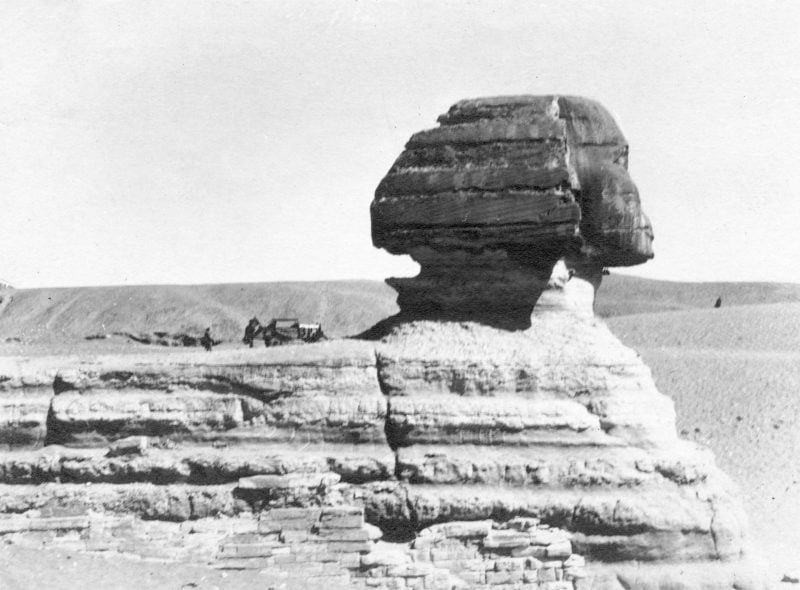

Aloha and Walter frequently pushed the boundaries of gender and dress, a fascinating aspect of the book. Walter used military clothing to convey professionalism, insisting that all of his crew dress in breeches and army tunics complete with Sam Browne leather belts. Photographs show that Aloha was seldom out of uniform except while in Egypt, where she was forced to wear a skirt so as not to offend more conservative locals. Her cross-dressing only became problematic when she was several months’ pregnant and was forced to wear maternity corsets to hide “her state” during performances.

Authors Christian Fink-Jensen and Randolph Eustace-Walden craft an amazingly detailed narrative from an impressive number of sources, the central strength of the book. The authors understood that the Wanderwells were masters of spin who cultivated their public personas as explorers and adventurers for profit. They also recognized that Aloha was interested in revising her own history later in life. Accordingly, they do not rely solely on her writings but consult newspapers, periodicals, third-party interviews, legal documents, and government files from a number of museums, archives, and repositories. Their research is complimented by a number of fascinating photographs of their expeditions, some taken by Walter and Aloha, which are interspersed throughout the text.

Not a lot of information is given about the personal relationship between Aloha and Walter, an omission that some readers may find unsatisfying. For example, little is known about Aloha’s 1926 disappearance from the expedition while touring in Massachusetts. She resurfaced in Miami some days later claiming she had left Walter a note to explain her absence. The authors suggest that this behaviour may have been because she was pregnant, an explanation that seems too simplistic given Aloha’s insistence in later years that she hitchhiked the distance. This is not entirely the authors’ fault, however, since Aloha was not above manipulating and fabricating facts about their private lives. In fact, she later destroyed her journal entries related to Walter’s mental health and his institutionalization in Geneva in 1923.

Despite this omission, Fink-Jensen and Eustace-Walden have compiled a remarkable biography about the exploits of a young woman from Vancouver Island and the charismatic man who guided her early career. In rescuing Aloha’s life from obscurity, they have reintroduced her as a significant and accomplished historical actor who was both a product and a purveyor of her times.

*

Bonnie Reilly Schmidt worked as a police officer with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police between 1977 and 1987. She returned to post-secondary education later in life, earning a BA from the University of the Fraser Valley (UFV), a Master’s from Simon Fraser University (SFU), and a Ph.D. in Canadian History in 2014, also from SFU. As a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada scholar, Bonnie Reilly Schmidt was also the recipient of the prestigious Dean of Graduate Studies Convocation Medal for Academic Excellence from SFU for her Ph.D. dissertation “Women in Red Serge: Female Police Bodies and the Disruption to the Image of the RCMP.” In 2014, she was also voted one of UFV’s Top 40 Alumni. Bonnie Reilly Schmidt has spoken at a number of academic conferences since 2005. She has written book reviews for BC Studies as well as articles for the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association and Canada’s History Magazine. Bonnie Reilly Schmidt has given numerous media interviews about women in the RCMP for Maclean’s, The Vancouver Sun, the Canadian Press, and Global TV (Vancouver). Her first book is Silenced: The Untold Story of the Fight for Equality in the RCMP (Caitlin Press 2015).

The Ormsby Review. More Reviews. More Often. More Readers.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

Comments are closed.