#30 Bob Bouchette, everyman scribe

Bob Bouchette’s last story, 1938

by Janet Nicol

First published October 21, 2016

*

Long before Allan Fotheringham or Eric Nicol, Vancouver’s most popular columnist was Bob Bouchette. The prolific non-conformist Bob Bouchette wrote literally thousands of columns, usually around 700 words each, mostly for The Vancouver Sun. His six-part series on the abysmal conditions of Vancouver’s relief camps during the Depression helped generate public sympathy and donations.

Bouchette was also a notorious drinker who allegedly once swam across Burrard Inlet to his home in West Vancouver with a bottle of rum tied to his neck. Ultimately he drowned to death in those waters when he was divorced and living in Kitsilano.

Born in Montreal in 1900 to a mixed French Canadian and Anglo family, Robert Dillon de Montenac Bouchette came to Vancouver in 1923 and, apart from a few years working in England, remained with the Sun from 1927 until his tragic and untimely death by drowning in 1938.

Few photos of Bouchette are available. Certainly the most eye-catching is one taken at The Bird’s Paradise, an aviary for 35 species of birds at the home of Charles E. Jones at 5207 Hoy Street. Jones later became Vancouver’s mayor in 1947.

Here Janet Mary Nicol recalls the life and the Byronesque death of this remarkable character from Vancouver’s Depression era. — Richard Mackie

*

Sometime during the night, on Monday, June 13, the heat wave had broken and Vancouver residents were breathing easier in their sleep. Above the shoreline at Second Beach inside Stanley Park, stood a group of men dressed in suits and fedoras.

Detectives Percy Pitt and Frank Maher were talking to reporters. One of the detectives pointed to a rock, east of wooden steps leading to the beach. It was the spot where the clothes were found. A number of papers were in one of the pockets. A man named George Sikora had found the clothes and called the police at 4:30 a.m. (1).

The detectives followed the prints of a bare man’s feet to the high water mark, where they disappeared. They made a thorough search of the shoreline, assisted by Del Shute, a lifeguard at the beach, but were unable to find the body. Still, the detectives were hopeful because the tide was at its lowest in the year which would help with the dragging.

The reporters’ pens moved quickly across the page of their notebooks. Bouchette, separated from his wife and employed with the Daily Province since April, was not among his colleagues covering the story.

That’s because he was the story.

Across from Stanley Park was the Point Atkinson lighthouse. The hazardous waters around the lighthouse, at the entrance to Burrard Inlet, were called “Sk’iwitsut,” meaning “turning point.”

The keeper of the concrete tower overlooking Sk’iwitsut was Ernest Dawes. He lived on the rocky site with his wife and children. He was up early on Thursday June 16, scanning the sky for clues to the weather’s mood.

Dawes was also in the habit of surveying the shoreline (2). In the course of his routine, Dawes found a body floating by the rocks at Star Boat Cove. He contacted the West Vancouver police.

When officers arrived, they rowed out to the sandy cove and recovered the body, identified as Bob Bouchette.

Police learned Bouchette had hailed a taxi near his rental suite in Kitsilano four days earlier, at about 2 a.m. Arriving to Second Beach, Bouchette had told the driver not to wait as he planned to walk home after a swim. The police believed Bouchette was overcome by the chilly waters as winds picked up and the temperature dropped.

There was no coroner’s inquest (3).

A non-denominational service was held at a funeral home chapel in Mount Pleasant. The chapel overflowed with people from all walks of life. A graveside service followed at Ocean View Cemetery in Burnaby (4). Bouchette’s sudden death, at age 38, reverberated for a long time among the many people who knew him.

Though the exact cause of Bouchette’s death remains a mystery, his fate is entwined with other casualties of the Depression, if only in a symbolic way. There was speculation among Bouchette’s colleagues, that depression and alcohol abuse may have led him to commit suicide (5).

*

The year 1935 brought dramatic protests to Vancouver’s streets. Bob Bouchette in his role as “everyman,” was there, as a witness and a storyteller who saw both sides of the social class divide.

At the mid-point of a bleak decade, Bouchette was an experienced reporter and columnist with a light touch, despite inner demons. Using the tools of his craft — a reporter’s pen, notepad and typewriter — he depicted a young city, its inhabitants and the depression era, with humour, insight and feeling.

Here we present five stories by Bob Bouchette from the year 1935, presented chronologically from January until August. The subjects range from the weather to the bloody Battle at Ballantyne Pier. This montage captures life in Vancouver at a time of economic and social crisis.

(i) Snow

The snow began falling across Vancouver in the predawn hours of January 21, 1935. Fresh snowflakes layered city streets and docks, weighed down boughs of cedar trees and filled the hulls of moored boats. Unemployed men shivered as snow seeped in to their makeshift shelters on empty land at Kits Point, once a First Nations reserve (1).

Downtown, snow fringed the windowsills of the abandoned Hotel Vancouver, construction halted years ago (2). Further east, elderly Chinese-Canadian men huddled within a heatless warehouse in Canton Alley (3). At Victory Square, the whitened grounds surrounding the cenotaph glistened in the dark. The roof of a four-storey building near the Square was blanketed, and above its entrance, snow laced a sign with the words, The Sun (4).

“That unmistakable creak,” Bob Bouchette had written in his newspaper column Lend Me Your Ears a few days earlier, “the sound which can not be duplicated, that noise of hard snow against the boot.”

West Coasters accustomed to mild weather and steady rainfalls were surprised when the temperature began plummeting January 9. The 34 year old Bouchette originally from Quebec, reacted with a sense of nostalgia (5).

“It made me immensely happy,” he confessed to Sun readers. “I saw again the scenes of my childhood, heard the tinkle of the sleigh bells, the ring of the skates on the ice, the shouts of boys playing hockey.”

“There is a tang to the air which quickens your step and clears your mind” (6).

By sunrise on Monday morning, 17 inches of snow had fallen on the port city of 250,000 inhabitants. Small boats sank, backyard sheds gave way and canned milk froze. The roof of the Hastings Park Forum collapsed.

Bouchette decided to walk to work, as many commuters did that morning, leaving his rented house in the West End where he lived with his wife Margaret and two children, Robert, aged 4 and Suzanne, aged two (7).

Making tracks in the snow, Bouchette passed by mansions, modest homes and occasional walk-up apartments, the smoky scent of fir rising from chimney stacks. Further along, a streetcar was marooned and the driver was shovelling snow off the tracks.

When Bouchette arrived at 125 West Pender, he climbed a flight of stairs to the newsroom. A spittoon was placed at the entrance and several oak desks lined the walls. The editors held command at the rim — with their desks in horseshoe-shaped formation. Bouchette gulped down a cup of coffee and lit a cigarette, after hanging up his coat. He eased into his chair and scrolled yellow copy paper into a manual typewriter, his restless, long limbs wrapped around the legs of his desk as he began pounding the keys.

Other reporters and editors were arriving late too. Upstairs in the composing room, the printers prepared the presses. By mid-morning the news room was filled with smoke, loud voices and the clacking of machines. Somewhere a half emptied bottle of scotch rolled inside a desk drawer (8).

The column could wait, an editor told Bouchette, directing him to make telephone calls to find out more about the storm. Doris Mulligan, among the few female reporters to work on a daily newspaper in the city, was assigned to write the storm story, putting together facts gathered from Bouchette and other reporters (9).

When the afternoon edition hit the streets, readers learned mills and logging companies along the Fraser River had been forced to shut down and more 2,000 men were temporarily out of work. Longshoremen at the Burrard docks were hampered lifting cargo off moored ships. The bitter cold “seems to sear the hands as though red-hot,” a dockworker said. Frost caused wooden paving blocks to expand and heave up in sections of the city.

Schools closed, giving students a reprieve from chilly classrooms and more time to toboggan down side streets. The Sunday night shift of telephone operators were anointed “heroines” for keeping the lines open all night and in to Monday morning, as they waited for their replacements to struggle in through the snow drifts (10).

The public was also reminded that “the poor” continued to need fuel and clothing.

The stock market crash that delivered an economic depression in 1929, resulted in Vancouver, usually a temperate terminal city at the national rail lines, taking much of the brunt. The province had the greatest number of transient, unemployed men relative to its population in Canada and in 1935, approximately 78,000 people in BC were on the relief rolls (11).

Reporters stayed with the weather story all week as the temperature began to rise and the thaw brought more havoc, especially in the Fraser Valley.

“Perhaps you will listen to one more crack about the cold wave,” Bouchette addressed readers of his column, “before it goes the slushy way of all Vancouver snows.”

He relayed the incident of a friend who slipped on an icy sidewalk. The fall caused his friend to reflect on life’s fragility.

“The cold snap has exerted a strong religious influence upon the people of Vancouver,” Bouchette — a lapsed Catholic — surmised. “There are all sorts of folks, pompous ladies and gentlemen who thought the world revolved for their own especial benefit. Now they know that they are helpless whenever Nature decides to put them in their place” (12).

(ii) The Waterfront

“Hot and sticky. The sky is overcast and there is hardly a breath of air,” Bouchette wrote in a depiction of the early afternoon of June 18 on the city’s waterfront. It was, he also noted, “the calm before a tropic storm of men’s passions” (1).

The lunch hour was almost over and Bouchette was talking with reporters from the rival dailies, the Daily Province and News-Herald, near the gate to Ballantyne Pier. He was hatless and wearing an overcoat that was falling apart. “That coat has become a dear companion, an ‘alter ego’ and ‘letter of introduction’ to many,” Bouchette declared in one of his columns. “There’s many an honest arm creaking beneath a ragged sleeve” (2).

A group of longshoremen’s wives and their children were milling near the gate too. Several males were clustered above the entrance. Bouchette noticed one of the men yawn.

Police Chief William Foster was standing on the south side of the railway tracks, flanked by three “motionless” RCMP officers. Foster was not in uniform, Bouchette observed, and wore a fawn raincoat and old fedora. “He looks almost languid,” Bouchette wrote. At Foster’s command were city police on horseback and many more on foot. Alongside them were mounted RCMP, some in sniper positions with machine guns and provincial police with billy clubs.

Further down, along Burrard Inlet, men were unloading cargo from vessels moored at Ballantyne Pier. The Shipping Federation had locked out 900 longshoremen two weeks previously and hired replacement workers, with the clear intention to break the union.

“My eye is fixed waveringly upon a gentleman in civilian clothes who is cocking a tear-gas gun six feet behind Foster,” Bouchette wrote. “I am only twenty feet away. I don’t like the look of that gas gun.”

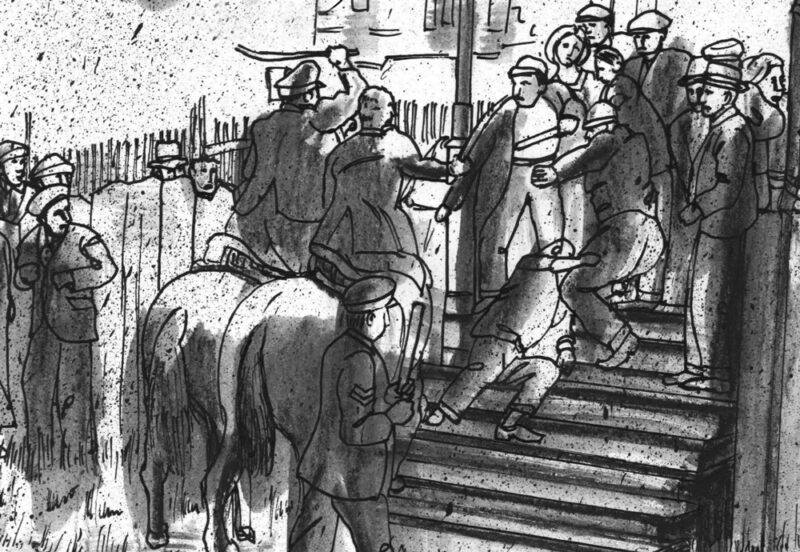

It was 1:20 pm when Bouchette heard singing. Longshoremen, a thousand strong, came in to view, marching down Heatley Street toward the gate, with the aim to confront the strikebreakers at Ballantyne Pier. A silence fell when the entire column came to a halt above the railway tracks.

“Just a minute boys,” Chief Foster said. He was “as cool as a cucumber,” according to Bouchette. Foster and a union leader exchanged words, then a fistfight erupted between another officer and striker.

Foster gave a signal by raising, then lowering, his arm. A high-pitched whistling sound followed as a canister hurled over the heads of the marchers.

“The sudden fear that gripped you when the man in the grey suit fired the tear-gas gun,” Bouchette wrote.

The strikers surged forward. Bouchette heard a marcher yell, “We’re going through.”

“All this happens in seconds,” Bouchette remembered. “I’m so scared that it seems like half an hour.”Another canister was hurled, and another, as police employed tear gas for the first time in the city’s history on the unsuspecting longshoremen — some of whom were veterans of gas attacks in the First World War.

The marchers began to flee as police rushed forward, swinging wooden sticks and leather-covered clubs, weighted with lead.“From behind the box-cars charge a squad of provincials on horseback,” Bouchette reported. “Screams and shouts and curses. Rocks are flying from behind me. Everybody begins running. The sight of galloping horsemen is truly terrifying.

Syd Williamson, a Sun photographer, held his large box camera steady, taking shot after shot of photographs, as tears rolled down his eyes.

“The police are laying to left and right with their batons. And quite suddenly the tracks are clear,” Bouchette continued. “But the battle has fanned out. It is proceeding in a hundred places in streets and lanes. You cannot get a picture of the whole — just flashes.”

Many longshoremen, supporters and even spectators were resisting the force of the police with fists, rocks and other weapons.

“A rock whizzes past my ear and smashes the window of a building behind me,” Bouchette wrote. He saw a frightened Japanese-Canadian man, who owned a corner store, lock his door and peer out the window.

“In a vegetable store nearby an elderly woman is waiting for an ambulance,” Bouchette also reported. “She has suffered a nasty blow on the back of the head. She says ‘I was trying to get some eggs and a mounted policeman told me to get off the sidewalk. I told him I was a taxpayer and he hit me with his crop.’”

The clash went on for almost three hours, sputtered out and flared up again until 5pm, when a stillness fell on the waterfront. Medical staff at two city hospitals were attending to injured police and civilians and the jail was filled with strikers.

When the dispute started, Mayor Gerry McGeer condemned the longshoremen and their “revolutionary” supporters within the Communist Party of Canada (CPC). The real issue, Bouchette countered in his column, was not communism but whether or not the union would be broken. “Middle-class folk — the white collar crowd — would probably welcome the smashing of the union,” he believed, “for white-collar wearers love taking it on the chin from the boss”(3).

“Some 800 of Vancouver’s longshoremen are men married, with families,” Bouchette also reasoned, pointing out these workers had been employed on Vancouver docks for five to forty years. “Are these the men who, we are told, are helping fomenters of revolution? The question does not merit a reply”(4).

The “Battle at Ballantyne Pier,” as the bloody afternoon is remembered, set the tone for a six month dispute ending in crushing defeat for longshoremen (5).

“I say to myself that I am pretty lucky to have remained in one piece,” Bouchette wrote in his eyewitness account, followed by “-30-” to indicate the article’s completion. It was late in the day when he stood up from his desk, but then long hours without overtime pay was standard practice in non-unionized newsrooms (6). Bouchette handed his copy over to the editor. It would not have been unusual for him — or any other Sun staffer — to contemplate a drink or two in a nearby pub, before heading home.

(iii) Eclipse

The advent of a lunar eclipse on the evening of July 15 was met with anticipation by sky-watchers in Vancouver. Starting at 7:12 pm, the moon would pass directly behind the Earth and into its shadow, aligning with the earth and sun. Bouchette planned to watch the spectacle atop the city’s highest elevation. At 152 metres above sea level, the former quarry of Little Mountain — its volcanic rock used to pave many of the city’s early roads — had become a popular lookout with a panoramic view of the downtown skyline, the inlet and mountains (1).

“I took along my dog,” Bouchette wrote in an article appearing on the front page of the Sun the next day, “hoping to extract a little story out of her reactions. We walked from my home in the West End and reached Little Mountain’s summit at 7:20, both perspiring.”

“Almost 100 persons, mostly in automobiles were already there, but we hadn’t missed anything. Back of the reservoir where the moon was, according to science, entering the penumbra, there was only a few wispy clouds and great banks of mist”(2).

There were also lots of mosquitos. “All over Little Mountain people are flailing away and slapping themselves,” Bouchette noted.

“I borrowed a telescope from a little girl, peered through it, but could see nothing.”

When Bouchette directed the telescope toward the north shore mountains, he saw a sun “dyed in blood.” It was about 8:09 pm and the moon was entering the umbra.

“Across the inlet, the entire sweep of mountains was bathed in magenta,” Bouchette wrote. “Far above, the clouds were long streamers of golden fleece against a luminous, endless blue. Smoke and mist almost concealed the city’s buildings.”

The mosquitoes were getting “fierce” as the sun disappeared behind the mountains and the sky turned a “sombre blue and grey.”

Bouchette also took note of the people around him. A little boy tumbled while picking blackberries. A mother holding her baby complained about paying taxes in a city filled with smog (3). Two men complained the “prime” park land they stood on would be better used for real estate development.

There was no sign of the moon at 9 p.m., just “blackness,” Bouchette observed when he looked skyward again.

Bouchette decided to leave, hiking down the hill “scented with clover, trees and flowers” accompanied by his dog. They were crossing the Granville Street bridge at 9:30 p.m. as the moon was coming in to the penumbra, concealed by smoke. By the time Bouchette reached the West End, a “thin edge of clear yellow appeared” and by 9:50 p.m., the moon had exited from the penumbra.

“Sunset steals Glory from shy moon’s eclipse,” was the headline of his article, summing up the lunar experience.

Bouchette estimated he and his canine companion had walked ten miles.

“We both felt tired and happy,” he concluded, “although the dog had no eclipse to howl at.”

(iv) Relief Camps.

Bouchette alerted faithful readers of Lend Me Your Ears he would be on a two-week vacation following his July 28 column. He reflected on his nine years working at the Sun, noting he had written 1500 columns in five years, at 700 words a piece (1). Bouchette also revealed his insecurities, doubting the value of his writing (2). His confession may have been brought on by the ‘blue devils,’ a feeling he once advised readers could be cured with a long swim (3).

Bouchette’s writing did have an impact despite his self-doubt, especially his investigations on the plight of relief camp workers (4). He wrote a four part series in the Sun in 1934 after visiting some of the 64 camps in BC. In a second series published in early 1935, Bouchette disguised himself as a ‘hobo,’ shaving his moustache and giving himself the alias of Frank Dillon (5).

In the process, Bouchette provided a west coast version of Jack London, The People of the Abyss (1903) and George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933).

*

Unemployed men “riding the rails” on their way in to Vancouver would start dropping off the train by the BC Sugar Refinery, near Ballantyne Pier. Those heading out of the city had to jump on to box car by Main or Gore Street, just before the train started picking up speed (6). Boarding trains without paying was illegal but became so common, the police often turned a blind eye.

Bouchette paid his train fare, however, as he headed out of the city to investigate the conditions of relief camps. A trip of several hours took him to the BC Interior. He was walking on a road near Sicamous, halfway between Vancouver and Calgary, when he met another man heading in the same direction.

“In the manner of homeless men we did not ask each other for names or personal information,” Bouchette wrote.

The pair agreed to ride a train together and Bouchette bought a bottle of rum for warmth against the chilly winter air.

“So a little way out of Sicamous we boarded a freight. The door of the car was partly open and we climbed in.”

This was Bouchette’s first experience as a passenger in a boxcar and he did not enjoy it.

“I can’t imagine a man being able to sleep in a boxcar even in good weather,” he reported. “Every bone of your body rattles if you lie on the floor.”

The two men moved around the car to stay warm. Bouchette learned his companion was heading to Calgary because he had argued with a foreman at a work camp “over the manner of doing a certain job on the road.” As a result, his name was put on a list and he was forbidden to work in any of BC’s relief camps.

“Let nobody tell you that there is no blacklist in the relief camps,” Bouchette wrote. He also learned the blacklist was getting longer, as men were removed from camps for pilfering, drinking and continued breach of regulations.

When Bouchette jumped off the train, he left his friend with the remainder of the bottle of rum (7).

On a visit to Camp 203 on the Deroche-Agassiz road in the Fraser Valley, Bouchette met relief camp workers who were widening and improving the highway. As with the workers in other camps, the men were given an allowance of 20 cents a day and room and board.

Bouchette joined the workers for a meal in the camp hall, describing it as “spacious, well-ventilated and clean” with long tables and benches. A poster on the wall caught Bouchette’s eye: “Please refrain from talking in Dining Hall.”

This regulation typified the atmosphere of the camps, Bouchette believed. When taken with the segregation and geographic isolation — and many of the men young — the conditions “get under their skin.” “They are, taking them as a class, about as merry and bright as men I’ve talked to in penitentiaries,” Bouchette observed (8).

“What a life,” a relief camp worker at another camp told Bouchette. “I used to get $75 a month and my board. I never though I’d get down to 20 cents a day.”

“There’s your whole camp in a paragraph,” Bouchette concluded (9).

The men’s discontent was harnessed by organizers of the Relief Camp Workers Union and on April 4, 1935 more than 5,000 men made their way to Vancouver in response to the union’s strike call. Bouchette supported their protest in his column, calling the camp system “vicious and retrogressive.” “This march on Vancouver, although it may be disturbing, is a mighty good thing,” Bouchette wrote. “It brings the evil of the camps to public attention”(10).

The workers occupied the city for almost two months, compelling Mayor Gerry McGeer to read the Riot Act at Victory Square as protestors demanded “work and wages.” On June 3, a thousand men led by Arthur Evans of the RCWU, jumped on box cars heading east, taking their grievances to the federal government, in a protest known as the On-to-Ottawa Trek (11).

*

Before signing off with his readers before his holidays, Bouchette concluded: “Shall I be doing the same thing five years hence? I do not know, of course, but if you continue to be as considerate of me as you have been in the past, I shall look back to this column-writing era with affection.

I now drop the tarpaulin over my machine and say au revoir.”

(v) Dancing

The terracotta trim on the upper wings of the Marine Building appear like sea foam on a majestic rock. The twenty-one story structure dominated the skyline and was a beacon to visitors arriving to Vancouver by sea. On its 16th floor, busts of King Neptune grace the four exterior corners and during the evening of August 21, the mythic figures watched over a vibrant scene on the street below (1).

Young men and women were streaming toward the building, like moths to the light. When they arrived, they danced.

Bouchette was standing apart, observing the “carnival” atmosphere (2). He estimated 12,000 to 15,000 people “coming and going” in a roped off area decorated with Japanese lanterns and coloured lights.

Musicians played inside a bandstand, erected at the north east corner of Burrard Street, and decorated with cedar leaves. A cluster of loud speakers magnified the music on to the street. Most of the couples dancing in to the night were young.

It was rare for Bouchette to compliment the Mayor, but in this instance he was compelled, calling the civic-sponsored event, “Gerry’s street dance.”

“They exuded such an atmosphere of spontaneous jollity,” Bouchette observed of the youthful participants, “that it made me feel almost lonely — and old.

*

Janet Mary Nicol is a secondary school history teacher in Vancouver and a freelance writer. She has written local histories about Vancouver and its people for BC History, Canada’s History, and Labour/Le Travail. She also volunteers with the BC Labour Heritage Centre. Visit her writing blog here.

*

Endnotes:

The Drowning

(1) The Sun, June 13, 1938, p. 1. The newspaper provided detailed coverage, following the police search to June 16, when Bouchette’s body was recovered.

(2) Donald Graham, Keepers of the Light: A History of British Columbia’s Lighthouses and Their Keepers. (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 1985), p. 74.

(3) The Sun, June 16, 1938, p. 1.

(4) The Sun, June 18, 1938, p.1.

(5) See Peter Stursberg, Extra! When the Papers Had the Only News for interviews (pp. 48-49) with Bouchette’s colleagues Cliff Mackay, Merv Moore, Mamie Maloney Boggs, and Norman Hacking. They recall Bouchette with affection and speculate on the circumstances leading to his death. See also “The Anarchist,” in Dean Jay Irvine, comp., Archive in Our Times: Previously Uncollected and Unpublished of Dorothy Livesay (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver, 1998), pp. 56-68. Livesay, (1909-1996) poet and social activist, was living in Vancouver when Bouchette died. She dedicated “The Anarchist” to him, a poem that imagines his drowning and suggests his alienation and defiance through symbols. Andrew Roddan (1882-1948), Minister at the First United Church in Vancouver’s east side in the 1930s, assisted and wrote about unemployed and homeless men living in “hobo jungles” in the 1930s. His eldest son Sam (1915-2002) recalled Bouchette in freelance articles he wrote in the 1990s. See Sam Burrows, Bob Hope Lives Here: A History of Vancouver’s First United Church (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2010), pp 50-69.

(1) Snow

(1) Todd McCallum, Hobohemia and the Crucifixion Machine: Rival Images of A New World in 1930s Vancouver (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2014), pp. 72 and 92. McCallum researched the “hobo jungles” around Vancouver in the 1930s. The Kitsilano Indian reserve of 37 acres in the False Creek/Kits Point area of Vancouver was established in 1869 by the British colonial government and occupied by local First Nations people until 1913. See http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/land-rights/mapping-tool-kitsilano-reserve.html

(2) See Bruce Macdonald, Vancouver: A Visual History. (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992), p. 42. Construction of the third Hotel Vancouver was started in 1928 and halted a year later, due to the economic downturn. The hotel wasn’t completed until 1939.

(3) Jill Wade, “Home or Homelessness? Marginal Housing in Vancouver, 1886-1950,” Urban History Review /Revue d’histoire urbaine, Vol XXV, No. 2 (March, 1997), p. 23. Yip Sang, a successful businessman in the Vancouver’s Chinatown, left his small fortune to his sons when he died in 1927. The family housed elderly, itinerant men in the warehouse, leased from the city.

(4) See The History of Metropolitan Vancouver by Chuck Davis on-line at

http://www.vancouverhistory.ca/archives_suntower.htm The Sun building was situated at 125 West Pender Street from 1912 to 1937. When a fire broke out, the newspaper moved to the Bekins building at 100 West Pender and the distinctive 17-storey structure was re-named the Sun Tower. Built in 1909 by the owner of the Vancouver World newspaper, the building had been sold to Bekins Moving Company in 1924.

(5) Robert Dillon de Montenac Bouchette was born June 11, 1900 in Montreal and baptized at the Basilique Notre-Dame. Source: ancestry.com. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection) 1621-1968 (database on-line). Provo, UT. USA ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2008. Bouchette’s French-Canadian father was a traveller in dry goods. Also in the Bouchette household in 1911 were Robert’s mother, older sister, maternal grandparents (of Irish-Scots heritage), and a female servant. Source: Year: 1911; Census Place: 6-St. Laurent Ward, Montreal St. Laurent, Quebec; Page 20; Family No: 243.

(6)The Sun, January 18, 1935, p. 6.

(7) Bouchette married Margaret Wyld in 1928. In 1935 and 1936 the couple lived with their children at 1320 Thurlow Street. The Bouchettes lived in nine other rented locations in the West End, Kitsilano and West Vancouver from 1928 to 1938, according to Vancouver city directories. About half of Vancouver’s residents were renters in 1931, a percentage which did not vary significantly throughout the decade. See Jill Wade, Houses For All: The Struggle for Social Housing in Vancouver, 1919-50 (Vancouver: UBC Press, Vancouver, 1994), p. 41.

(8) Peter Stursberg, Extra! When the Papers Had the Only News, Sound Heritage Series, Number 35, 1982. Oral accounts of reporters and editors who worked on Vancouver and Victoria newspapers include descriptions of the functioning of the news room, its colourful characters and “drinking culture” during the 1930s. See also BC Archives, Sound Heritage Series, No. 35, Accession No. T3819, Transcript 3774-12, page 8. Pat Slattery began at the Sun as a copy runner in 1930 and fondly recalled Bouchette’s work habits and personality.

(9) The Sun, January 22, 1935, p 6. In his column, Bouchette described the process of putting together the article about the storm.

(10) The Working Lives Collective, Working Lives: Vancouver 1886-1986 (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1985), p. 15. Statistics provided to the authors from the BC Department of Labour, Annual Reports.

(11) The Sun, January 19, 1935, p. 1 and January 21, 1935, p. 1 provides detailed articles on two Vancouver snowstorms. Also see Helen Borrell, “Silver Thaw — Fraser Valley’s Paralysis of Ice” in BC Historical News 25: 1 (Winter 1991-92), pp. 11-14.

(12) The Sun, January 21, 1935, p. 4.

(ii) Waterfront

(1) The Sun, June 19, 1935, p. 1 and p. 6. Bouchette’s article ran on the front page along with a second article by colleague Pat Terry. A few of Bouchette’s eyewitness descriptions are also taken from Bouchette’s column published on the same day. Additional details about the conflict are in The March to Ballantyne Pier, by Janet Mary Nicol, Labour Heritage Centre. http://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/2015/06/18/the-march-to-ballantyne-pier-18-june-1935/ See also Andrew Parnaby, Citizen Docker: Making a New Deal on the Vancouver Waterfront, 1919-1939 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008).

(2) The Sun, February 19, 1935 p. 4. Bouchette wrote about his raincoat in his column.

(3) The Sun, June 6, 1935, p 6. Also see Stephen Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930–1936 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012) Endicott examines an arm of the Community Party of Canada, the Workers’ Unity League, which includes the WUL activists’ involvement in Vancouver’s longshoremen’s strike and relief camp workers’ protests.

(4) The Sun, June 7, 1935, p. 6.

(5) The longshoremen succeeded in forming an independent union in 1945. The International Longshore Workers Union (ILWU) have since erected a cairn at New Brighton Park on the city’s east side waterfront in remembrance of the Battle at Ballantyne Pier.

(6) Stursberg, Extra! When the Papers Had the Only News, pp. 73-81. Reporters discussed organizing a union in the late 1930s, eventually joining the American Newspaper Guild and achieving a first contract at the beginning of the Second World War.

(iii) Eclipse

(1) Harold Kalman and Robin Ward, Exploring Vancouver: The Architectural Guide (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre), 2012, p. 90. An open-air reservoir was built in the 1920s, providing the city’s drinking water and has continued to be structurally upgraded over the decades. The city developed the urban land into 52 hectare (130 acre) of green space, named Queen Elizabeth Park.

(2) The Sun, July 16, 1935, p.1 provides Bouchette’s account of the eclipse.

(3) The city’s smog came from smokestacks of factories and saw mills along the shoreline of False Creek and downtown.

(iv) Relief Camps

(1) The Sun, June 16, 1938, p. 11. Bouchette came to Vancouver in 1923 and worked on the Sun. He travelled to England in 1925 and when he returned to Vancouver in 1927, re-joined The Sun.

(2) The Sun, July 29, 1935, p. 4.

(3) The Sun, July 12, 1935, p. 6.

(4) The BC government set up its first relief camp in 1931 and a year later, the federal Department of Defence took control of 144 relief camps across Canada.

Department of National Defense (1937). Final Report of the Unemployment Relief Scheme for the Care of Single, Homeless Men Administered by the Department of National Defense, 1932–1937, Vol 1. A.G. (McNaughton Papers), M.G. 30 Series II Vol 98. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. See also Lorne Brown, When Freedom was Lost: The Unemployed, the Agitator, and the State (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1987).

(5) Bouchette’s first series on relief camps made the front pages of the Sun February 20- 24 1934 and his second series was published January 2-5 1935.

(6) See Rolf Knight, Along the No. 20 Line: Reminiscences of the Vancouver Waterfront (Vancouver: New Star Books, 2011), p. 69-70. Knight’s father rode the rails in and out of Vancouver in the 1930s. “There’s no romance in it. Never try it,” he told his son.

(7) The Sun, January 3, 1935, p. 1.

(8) The Sun, February 22, 1934, p. 1

(9) The Sun, January 4, 1935, p. 2.

(10)The Sun, April 4, 1935, p. 4.

(11) See Ronald Liversedge in Victor Hoar, ed., Recollections of the On-to-Ottawa Trek (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1973). Liversedge was a trek participant. The federal government closed relief camps in June, 1938. On the 75th anniversary of the trek, a plaque commemorating the event was placed on the railing of the bridge to Crab Park. Situated at the north end of Main Street, the bridge is above the train tracks where the relief workers boarded CPR boxcars. The trek’s historical society website is at http://www.ontoottawa.ca/home.html

(v) Dancing

(1) Kalman and Ward, Exploring Vancouver, pp. 145-46. Construction of the Marine Building began in 1929 and was completed in 1930.

(2) The Sun, August 22, 1935, p. 6.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster