#29 Althea Moody and All Hallows

ESSAY: Across the Bright Continent: Althea Moody, Missionary and Artist in Western Canada

by Jennifer Iredale

First published October 21, 2016

*

Missionary, linguist, educator, and artist Althea Moody (1865-1930) spent twenty years (1891-1911) teaching at the Anglican Church’s All Hallows School in Yale. This school admitted both “Indian” and “White” girls, making it exceptional and unusual in the history of education in early BC.

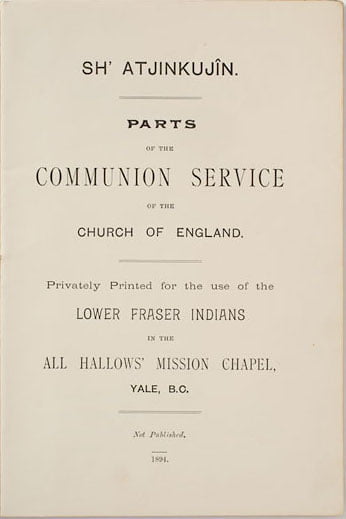

Largely forgotten, Althea Moody, the daughter of a London-based official with the Canadian Pacific Railway, wrote a rarely-cited book while a teacher and missionary at Yale: Sh’Atjinkujin: Parts of the Communion Service of the Church of England, Privately Printed for the Use of the Lower Fraser Indians in the All Hallows Mission Chapel, Yale 1891 (London: Darling & Son, 1894).

In keeping with her modesty and religious humility, Moody did not allow her name to appear on the title page, but her authorship makes her one of the first women to produce a book based on her experiences in BC. For more information on Althea Moody, see the extended entry on her in Canada’s Early Women Writers.

Here Jennifer Iredale examines some of Moody’s experiences as a Victorian educator, missionary, artist, and linguist who translated part of the Anglican service into the Nlaka’pamux and Halkomelem languages. Iredale assesses Moody’s life and career, illustrated with images from the watercolour travel journal she kept 1891, when she was 26, along the main line of the Canadian Pacific Railway. They are published here for the first time courtesy of the Community of All Hallows in Ditchingham, Norfolk, England — Ed.

*

“Across the Bright Continent” is an unpublished postcard-size watercolour travel journal painted in 1891 by twenty-six-year-old Althea Moody as she journeyed from England to Yale, British Columbia, where she would spend the next twenty years doing missionary work and teaching at All Hallows in the West.[1]

Moody recorded her first impressions of Canada during her journey sponsored by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) — images that include buffalo bones piled on a prairie horizon, the Rocky Mountains from the Banff Springs Hotel, and scenes of a dramatically cascading Fraser River. The thirty-nine images captured her first impressions of Canada, an expanse she refers to as the “bright continent.”

Piecing together Moody’s biography proved challenging. Apart from the anonymity in researching women’s history, an added difficulty with reconstructing Moody’s story was that, in keeping with her ordination into the “hidden life”[2] of an Anglican nun in 1901, no substantial information about her life was to be found in the archives. Historians at All Hallows Convent in Ditchingham were able to tell me that Sister Althea “was the daughter of one Mr. Moody who was connected with the Canadian Pacific Railway, and he gave us [All Hallows employees] free or reduced tickets for the journeys across Canada.”[3] The quest to discover more of Moody’s story, prompted by coming across her watercolour journal, began with this small but intriguing piece of information.

Although Moody was a competent watercolourist who strove to capture in her paintings her response to the wild and changing landscape of Canada, her passage was not sponsored for artistic reasons, but for the relationship between the CPR, her father, Old Etonian Harry Moody, M.A., and the Anglican mission efforts in the new world. Harry Moody was a strong supporter of All Hallows — both in England and in western Canada.[4] His connection with the CPR, and his position as trustee of the school, ensured that the CPR sponsored rail travel for those associated with All Hallows for many years.

In 1891, the year in which Moody travelled across “the bright continent,” the England census lists her as being the eldest of Harry and Florence Moody’s nine children.[5] Despite her Englishness and her English education, Althea and her family had deep and substantial Canadian connections. Her parents met in New Brunswick where Harry was serving as Secretary to the Governor of New Brunswick in 1861.[6] Florence Parker[7] and Harry Moody were married in 1863 at the Anglican Cathedral Church in Fredericton.[8] Althea Moody was born in Fredericton on 1 June 1865 and spent her childhood in the Atlantic provinces.[9]

By 1881 the family was residing in England and Harry Moody was working as “Ass. Secretary Gov. of Canada.”[10] Althea, now sixteen, was a scholar and boarder at St Anne’s College, Abbots Bromley, Staffordshire — an Anglican girl’s school with strong missionary leanings.[11] A decade later she was recruited by Sister Amy, Mother Superior at All Hallows in the West at Yale, BC, to undertake teaching and mission work.[12]

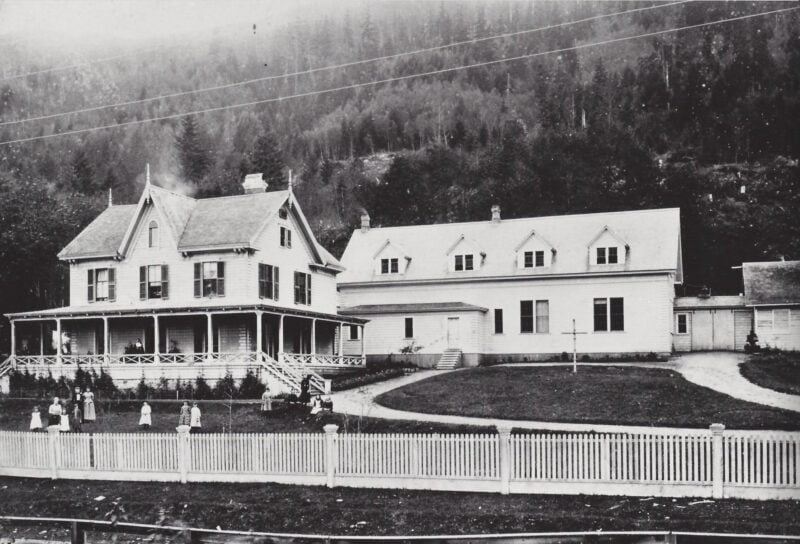

Many students, native and non-native, and all female, received their education there between 1885 and 1916. The Sisters from the Community of All Hallows, Norfolk, began their “parochial mission work among the Indians” at Yale in 1884, establishing an “Indian Mission School for girls with 30 pupils” in 1885, and in 1890 what they termed a “Canadian Boarding School for girls, 30 pupils.”[13]

The school magazine outlined the colonial and religious values that led to the founding of the “Indian school” and identifies the training that was thought appropriate for “educating and Christianizing” the students:

Some fourteen years ago Bishop Sillitoe induced the All Hallows’ Community at Ditchingham, Norfolk, to attempt the task of educating and Christianizing the girls of the Indian tribes on the Fraser River, and he established the Sisters at Yale.… We may briefly say it [the fee-based school for non-native girls known as the “Canadian” school], was originally started partly that, by the fees of its pupils, the missionary and educational work among the Indians might be supported, and partly because there are no distinctly religious schools in the diocese to which the clergy could send their children…. The two schools are kept entirely distinct, except in worship….

In the Indian school there are some thirty girls. Many more could be obtained if funds and accommodation permitted.… The girls are carefully trained in all practical and domestic work, being promoted as aptitude is shown in cooking and baking. Gardening, too, they take a share in… [14]

Althea Moody proved to be a real “catch” for the community of women at All Hallows in the West. Her youth, English boarding school education, Anglican upbringing and missionary zeal, and her father’s patronage made her an ideal candidate for the post. Beyond this, she possessed abilities as artist, linguist, healer and writer — abilities that she put to good use at Yale and that are evident in her material legacy, including her hitherto unpublished watercolour journal, “Across the Bright Continent” (1891), her book, Sh’Atjinkujin: Parts of the Communion Service of the Church of England (1894), and in articles published in the school’s quarterly journal during her time there.

In “Across the Bright Continent,” she paints her way across the land of her birth. Its preservation in the Archives at All Hallows in Ditchingham provides some evidence that it was, and is, valued by the community there, perhaps providing those in the “old country” with visual images of Canada as seen by one of their own. However, this little art journal also allows us to explore the possibility that Moody was influenced and inspired by her father’s association with artists through the CPR art patronage program: between 1883 and 1903, as Secretary to the CPR in London, Harry Moody promoted the CPR overseas and worked closely with CPR General Manager William Cornelius Van Horne and his program of art patronage.[15]

The CPR constructed a vast transcontinental railway line across North America to fulfill a confederation promise made by Canada to British Columbia. Completed in 1885 under Van Horne’s direction, the CPR launched an intense advertising campaign to encourage immigration and settlement along the over 3000 miles (4828 kilometres) of rail line that ran through what was, to Europeans at least, a vast wilderness. The purpose of this campaign was to raise much-needed income from the sale of these lands to service the construction debt and to manage the onerous operating costs of the railway. Art historian Allan Pringle notes that Van Horne “adopted a policy of offering free transportation to the West Coast and back to any artists whose work would serve the Company’s interests.”[16]

Harry Moody, at Van Horne’s direction, provided artists with funds and free train passage across Canada in exchange for paintings of landscapes which the CPR intended to promote immigration, settlement, and tourism.[17] From his London base, Moody helped organize exhibitions of these Canadian paintings.[18] He was familiar with the work of Canadian painters such as Lucius Richard O’Brien and John Arthur Fraser — who both received passage and funds from him. Moody and Van Horne also sponsored John Arthur Fraser’s work, and in 1887 organized a vernissage, a private viewing of Fraser’s work, attended by London high society. [19]

Moody and her family departed England for Canada on 6 July 1891, leaving Liverpool along with 288 passengers on board the Vancouver.[20] Her watercolour journal begins with the ship’s departure, with a painting entitled Last View of the Old World from my Porthole, August 7.

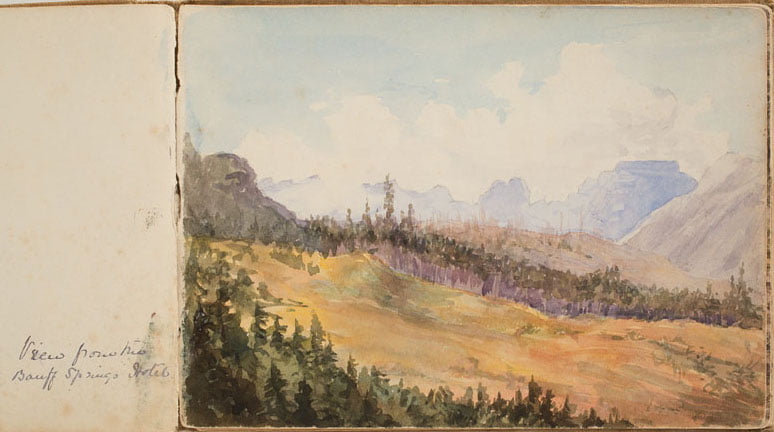

The next page of Moody’s journal shows her first view of the New World off the coast of Labrador, followed by images painted from the Vancouver as it made its way from the Atlantic into the St. Lawrence River. The Moody family disembarked the Vancouver on its arrival in Quebec City on 15 August, almost six weeks after leaving England, and then boarded a CPR train to continue their journey west to British Columbia. Moody’s watercolour journal documents this trip with paintings of the ancient rocks and numerous lakes of the Canadian Shield, and around Thunder Bay, then on across the prairies with paintings of wheat fields, piles of buffalo bones, and alkali lakes. When the train reached the Rocky Mountains, the Moody trio disembarked for a few days.

[M]edicinal watering-place and pleasure-resort…. No part of the Rockies exhibits a greater variety of sublime and pleasing scenery; and nowhere are good points of view and features of special interest so accessible…. The railway station at Banff is in the midst of impressive mountains .… A steel bridge takes the carriage-road across to the magnificent new hotel, built by the railway company near the fine falls in the Bow and the mouth of the rapid Spray River. This hotel, which has every modern convenience and luxury, including baths supplied from the hot sulphur springs, is kept open during the entire year. It is most favourably placed for health, picturesque views, and as a centre for canoeing, driving, walking or mountain-climbing.[21]

Moody’s first Rocky Mountain painting is titled simply View from the Banff Springs Hotel, a view that was favoured by many of the CPR artists.[22]

Another five paintings in Moody’s journal depict the Rocky Mountains. She was clearly impressed by the mountains, as were many of the artists under the patronage of Van Horne and the CPR. Her Rocky Mountain paintings suggest that she shared with Emily Carr a similar painterly response — as each attempted to convey the immensity of the landscape that is so characteristic of the Canadian west. [23] Moody’s impressions can be surmised from what the (official) CPR-sponsored artists wrote about the grandeur and the wildness of this landscape. In 1887 Lucius O’Brien, commented that, “The mountains are as high but the valley is wider, and they stand off to be admired instead of towering over one’s head. There is no want of grandeur, but one is filled with a sense of beauty, rather than awe.”[24]

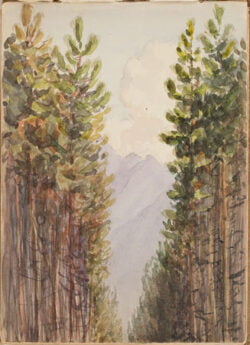

Moody’s view from the hotel is followed by a watercolour titled A Forest Path, an image that gives the impression of looking up through the vertical brown-barked trunks of tall pines to green branches moving expressively against the sky. Through this alleyway of trees — reminiscent of Emily Carr’s later Among the Trees — the Rocky Mountains can be glimpsed below a clouded sky.

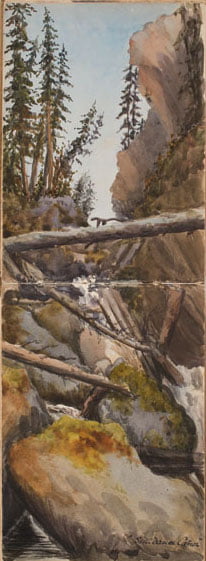

Another in this series is Sun Dance Cañon, a dramatic vertical painting where Moody has turned the journal to allow the use of two pages on a long axis and provide a larger surface to convey the dramatic subject matter. The viewer is invited to look up from the river cutting through the canyon below, past the walls of rocks and trees, to the bright blue sky overhead, and one can almost hear the sound of the river running through the canyon, and imagine the slippery feel of the moss-covered rocks. This painting vividly portrays the force of the river, the trees leaning in at the top of the canyon, and the tumble of trees and branches crowding the middle ground.

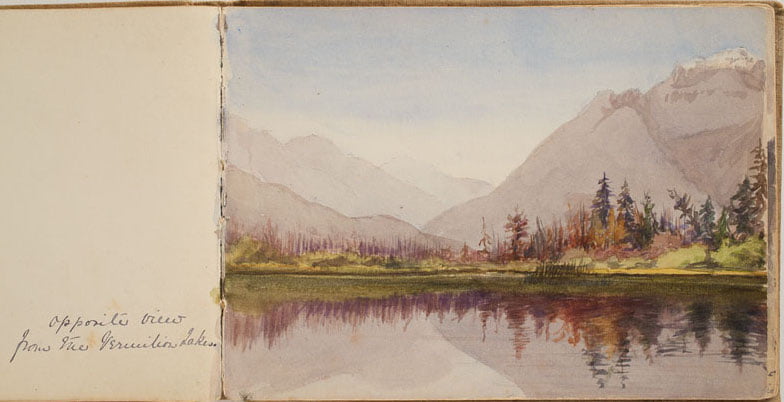

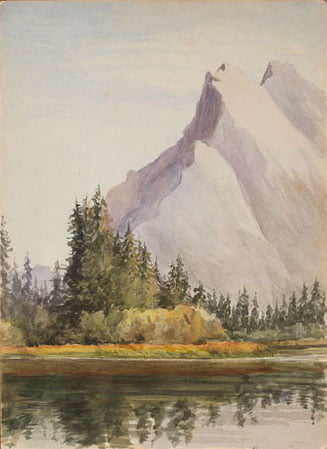

The following painting in this series, The Twin Peaks Mountain from the Vermilion Lakes, Banff, is a picturesque composition featuring Mount Rundle, with one of the three reflective Vermilion Lakes in the foreground, a huddle of coniferous forest in the middle ground, and the dramatic planes of the mountain filling the top right. Similarly, the next watercolour, Opposite view from the Vermilion Lakes, draws the eye to the massive mountain in the background by way of reflections in the water in the foreground, through a forest in the middle ground. Moody, like so many nineteenth century artists sponsored by the CPR, favoured these views of Mount Rundle and Vermilion Lakes.

Following their respite at Banff, the Moody family continued their journey through Roger’s Pass by way of the recently established Glacier National Park — where they reached an elevation of 4,360 feet — to arrive at their next stop, the CPR’s Glacier House Hotel. The 1888 CPR timetable describes this stop as:

Station and hotel within thirty minutes walk of the Great Glacier, from which, at the left, Sir Donald rises, a naked and abrupt pyramid, to a height of more than a mile and a half above the railway. This stately monolith was named after Sir Donald Smith, one of the chief promoters of the Canadian Pacific Railway.… The hotel is a handsome structure resembling a Swiss chalet, which serves not only as a dining station for passing trains, but affords a most delightful stopping place for tourists.… No tourist should fail to stop here for a day or two.[25]

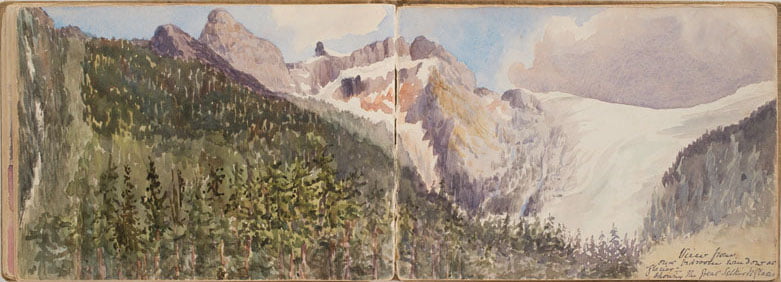

View from our bedroom window at “Glacier” — Showing the Great Selkirk Glacier, the last of Moody’s Rocky Mountain paintings, once again required a double-page spread, this time arranged horizontally, to better capture the drama of the mountains. Moody’s confident brushwork captures the beauty and grandeur of the mountains from the comfortable confines of her bedroom vista.

Moody continued to be captivated by these mountains and returned on painting excursions through her years in British Columbia. On 10 August 1892, an anonymous All Hallows travelling companion penned a letter from the Glacier Hotel, later printed in East and West, the All Hallows magazine published by the order in England:

Miss Moody and I have come up to this lovely retreat among the mountains, under the shadow of the great Glacier of the Selkirks, to rest and recoup for a few days. The Glacier Hotel is very very quiet — there are half a dozen ladies and children, and a few men, chiefly artists, staying here. There is not another habitation within twenty miles; the only means of approach or departure is by the railway line. The passenger trains “East-bound” and “West-bound” only arrive once a day.… The solemn silent beauty and grandeur of the mountains satisfies one, and brings a sense of nearness to God. Miss Moody has been making some lovely sketches. She has begun a series of Mission Sketches, including churches, ranches, camps, &c. Wherever we stopped, and the light was sufficiently good for sketching, she took advantage of it.[26]

This letter indicates the range of Moody’s work – most of it now, alas, lost – and suggests that she was familiar with the artists who were engaged with painting the Canadian landscape. At the Glacier Hotel in 1892, and on her trip across Canada a year earlier, her visits overlapped or coincided with artists such as Frederic Bell-Smith, Willam Brymner, and Lucius O’Brien, and photographers such as Bailey and Neelands and Notman.[27] Through her father, it seems likely that she knew who they were and what and where they were painting. Moody’s paintings are so similar in style and chosen subject matter to those of the artists painting under CPR sponsorship that it seems more than plausible that she was influenced by them.

The last few watercolours in “Across the Bright Continent” are of the lower Fraser River region, where Moody was to live for two decades. Here too, the descriptive notes in the 1888 CPR timetable give us a sense of what Moody encountered as she traversed the Fraser Canyon for the first time:

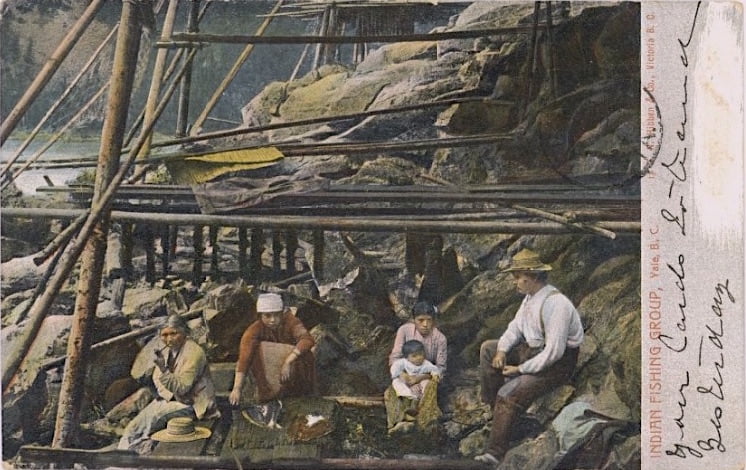

The canyon alternately widens and narrow. Indians are seen on projecting rocks down at the water’s edge, spearing salmon or scooping them out with dip-nets, and in sunny spots the salmon are drying on poles. Chinamen are seen on the occasional sand or gravel-bars, washing for gold; and irregular Indian farms or villages, with their quaint and barbarously decorated grave-yards, alternate with the groups of huts of the Chinese.[28]

At North Bend, where the train was scheduled to stop, travellers were informed that “a charming little hotel makes a desirable and delightful stopping-place for tourists who wish to see more of the Fraser Canyon than is possible from the trains.”[29] Further down the river, at Moody’s destination of Yale, the CPR timetable provides a population of 1,200 and calls the town:

[T]he head of navigation and an outfitting point for miners and ranchmen northward. It occupies a bench above the river in a deep cul de sac in the mountains, which rise abruptly and to a great height on all sides. Indian huts are seen on the opposite bank, and in the village a conspicuous Joss house indicates the presence of Chinamen, who are seen washing gold on the river bars for a long way below Yale.[30]

By the time of Moody’s arrival, the town had already had a short but significant history in colonial British Columbia. Joan Schwarz and Lilly Koltun, in their analysis of five nineteenth century views of Yale, note that:

Yale was firmly fixed in the nineteenth-century British Columbia psyche as a place of note, and it sustained this reputation despite rising and falling economic fortunes. Its fate was inextricably tied to its location — first at the head of steamboat navigation on the lower Fraser, later on the wagon road to the Interior and then on the transcontinental railway.… As Hudson’s Bay Company fort, gold rush community, service town, supply depot, trans-shipment point, surveying headquarters and railroad construction centre, it continually commanded attention as a place that was or had been “interesting” or “important” or “remarkable” in some way.[31]

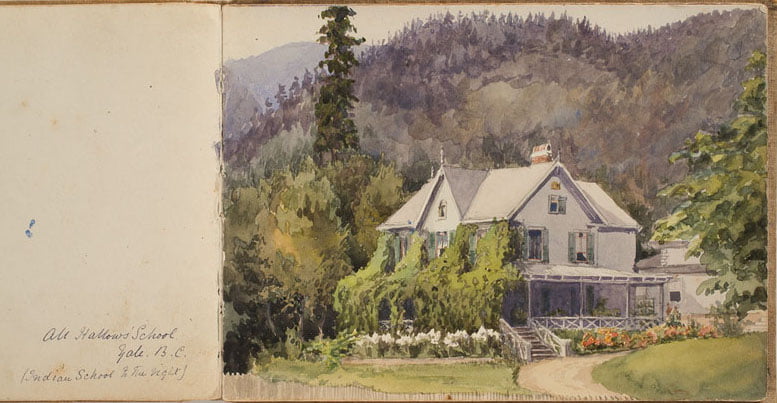

Moody would live in what had been the house, the quaintly named “Brookside,” of CPR contractor Andrew Onderdonk, which was purchased and refashioned to accommodate All Hallows School, which officially opened in 1890. Indeed, Richard Maynard’s well-known 1881 photograph of Yale was taken from Onderdonk’s house, and Maynard’s image was used as the basis for Lucius O’Brien’s engraving Yale, published in Picturesque Canada, in the autumn of 1884.[32]

Another view of Yale at the time of Moody’s arrival was that painted in 1886 by the popular nineteenth century artist William Brymner, and purchased by Sir George Stephen, the first president of the CPR.[33] This striking image, dominated by Mount Lincoln in the background, shows one of the sisters from All Hallows standing on the left bank of the Fraser River while, beside her, three First Nations girls are “completing their morning toilet.”[34]

Given the interconnections between the family, the railway, and the artistic preoccupations of the sponsors and the artists, Moody must have been aware of such iconic renderings of Yale.

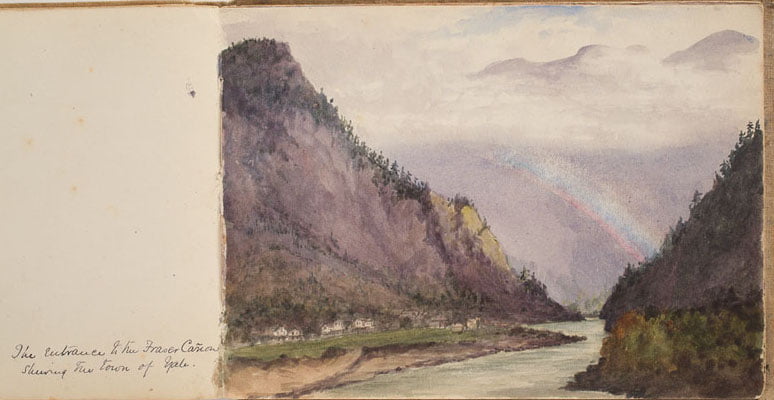

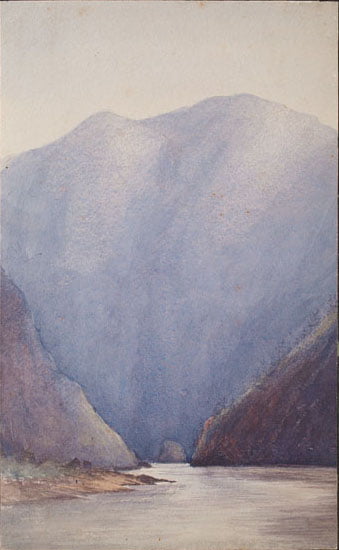

Schwartz and Koltun remind us that “entrenched in the British Columbia consciousness was a visual image of Yale.… One view came to epitomize the town. A curve in the river just downstream from the settlement afforded a convenient and unobstructed vantage point from which at least a dozen renderings of Yale were made in the half-century after British Columbia became a colony in 1858.”[35] Moody was equally enamoured by this aspect of Yale. One of her journal paintings, The entrance to the Fraser Canyon showing the town of Yale, shows this iconic view: a picturesque painting depicting the bend in the river with the town of Yale clustered on the left in the shadow of Linky Mountain, and a rainbow arching over the river beneath misty clouds.

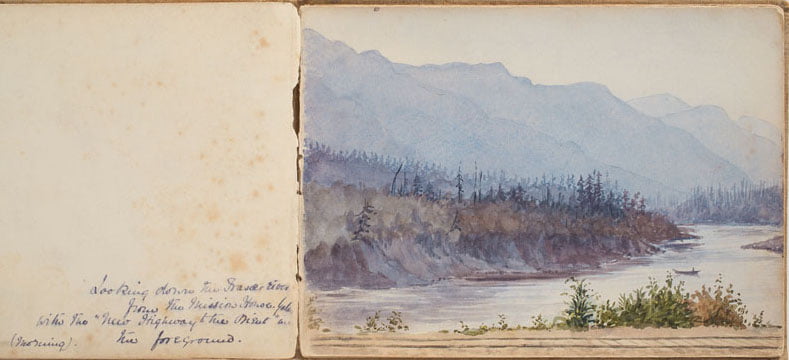

Another of her 1891 watercolours, Looking down the Fraser River from the Mission House, Yale with the new Highway to the Orient in the foreground, shows the railway line in the foreground. Her caption, “The New Highway to the Orient,” echoes a CPR publication.[36] Of the view from this spot, Schwartz and Koltun note that “the landscape elements came together in the proper mix and proportions to satisfy the nineteenth-century obsession with the picturesque.”[37]

The next painting in Moody’s 1891 watercolour journal, a beautiful little image titled All Hallow’s School, Yale, B.C. (Indian school to the right), which Moody would call home for close to two decades (reproduced at the top of this essay — ed.). Painted with meticulous detail, it shows a large frame building with a deep verandah, in the midst of lush gardens made to look very inviting. Moody may have sketched the building in pencil before painting it, but her familiar freehand and impressionistic brushwork is evident in the background of trees and the forested mountain.

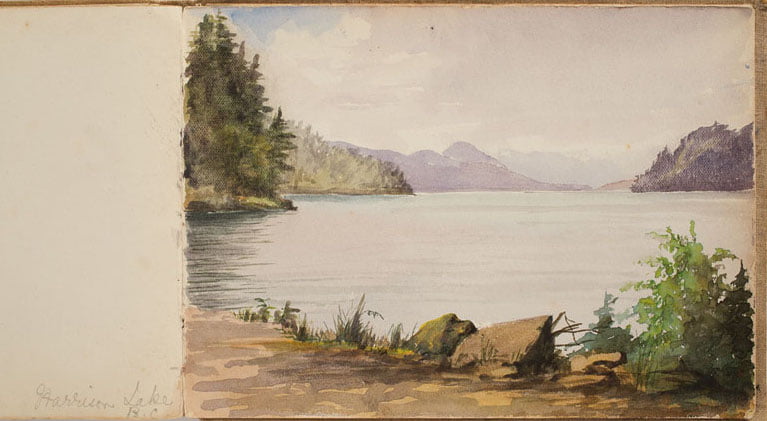

Harrison Lake, B.C. is the last painting in the watercolour journal. It seems likely that the Moody family travelled the few miles and one-hour train ride from Yale to Harrison to visit the famous hot springs and fine hotel on the shores of the Lake, before Moody took up her teaching post at All Hallows in the West. “Agassiz,” notes the 1888 CPR timetable, “overlooked by Mt. Che-am, is the station for Harrison Springs (hot sulphur), on Harrison Lake, five miles north. These springs are famed for their curative properties, and are visited by invalids from everywhere on the Pacific Coast. A good hotel affords accommodations, and the country about is most interesting.”[38] Here, Moody has produced a romantic image showing the quiet water of the lake with a walking path in the foreground, and the mountains, purple and then blue, recede into the distance. Forested hills executed with a loose brush style create interest on both sides of this composition.

“Across the Bright Continent” is more than a linear chronicle of Moody’s first encounter with the many and varied landscapes that unfolded before her eyes as she travelled by train across the vast reach of Canada. With each new image it reveals that, as Moody approached her destination, she was better able to convey the grandeur and scale of the mountains, rivers, and lakes that comprise the nineteenth century perceptions of the landscapes of Canada’s west. Despite the limitation of the 3 x 5 inch paper posed by the medium of the journal, her compositions are evocative and her brushwork expressive.

With her disembarkation at Yale, Althea Moody took up her role at the School. “Miss Moody” is identified as the painting and drawing instructor in the curricula published with each issue of All Hallows In the West.[39] By all accounts her art distinguished her at the school. According to Sister Violet of All Hallows in Ditchingham, Moody became a very popular teacher and was remembered for conveying her gift for watercolour painting to her students.[40] In a letter written in 1901 and published in All Hallows in the West, a friend asked, “is your brush as busy as ever?”[41] It is likely that Moody painted the “two water coloured sketches of views down the river” that were featured on the “specially beautiful ‘home-made’ cover for the printed copy of the ‘Song of Welcome’” requested by the Duke and Duchess of York as a memento of their stop at All Hallows school in late September of 1901. More of Moody’s paintings will undoubtedly come to light.

Althea Moody also worked with the First Nations children at the school and conducted missionary work among the Fraser Canyon First Nations. The material legacy of this work is a translation of part of the Anglican service published in London in 1894 as Sh’Atjinkujin: Parts of the Communion Service of the Church of England and a number of articles in the quarterly journal of All Hallows in the West.[42] In her first years at Yale, she concentrated on learning the languages of the local First Nations and prepared Sh’Atjinkujin which, despite being published by the Church of England, was in fact her work, as the Monthly Report on the Diocese of British Columbia announced in 1895:

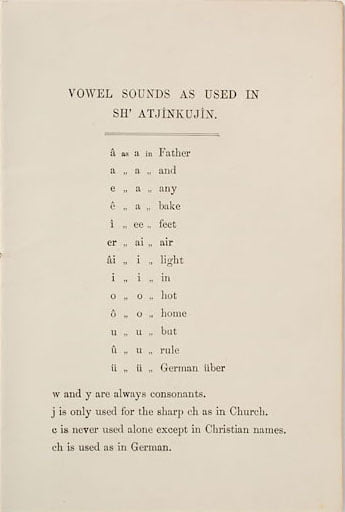

Under this title [Sh’Atjinkujin]Miss Moody has brought out a translation of the Holy Communion Office into the language of the Lower Fraser Indians. It will be of great use to have this in convenient printed form, and the pamphlet has been drawn up with care and an evident knowledge of the subject. There is an explanatory introduction showing the method of pronouncing the vowels. To the unlearned in this language it will seem a very difficult tongue to pronounce, as the following translation of the first Commandment will show: Quil Jijil Shiam Squaljit tik ila squals quis thutj; E jiliwa I ta eltha Shiam quil Jijil Shiam.[43]

Moody must have had considerable linguistic ability to learn enough of the local Salish language to make this translation. She may employed the Chinook pidgin language which was then in common use. However, in the quarterly journal she expressed her frustration at her inability to communicate with her students. “It is difficult,” she wrote with considerable humility and understatement, “not to say impossible, to attempt anything in the way of religious instruction, when one sees how ludicrously one fails to make tangible every-day matters understood. The few words we have in common are so hopelessly inappropriate and inadequate to express even the most rudimentary spiritual ideas.”[44]

Moody’s cri de coeur reveals a sensitivity to the complexity of spoken Salish and the difficulty of communicating between the two cultures. In another entry in All Hallows in the West, she lamented, again with empathy and understanding, that:

But even after years of teaching, [they show] most curiously by their superficial knowledge of English that it is indeed a foreign language to them. Their own language, though most complex in moods, senses and inflections of all kinds, is yet unwritten, and while they have sounds which we cannot represent with our English alphabet, yet some of our sounds seem perfectly bewildering to them.[45]

In the course of her two decades in Yale, “Miss Moody” worked closely with Indigenous communities and shared some of these experiences in All Hallows in the West. Written for patrons and benefactors of the school in England, the journals contain snippets of information on life in the nearby Sh’Atjinkoojin (Yale) and Nktakapamuk (Thompson) communities.[46]

For example, in 1900 the journal noted that, “For three months in the year, that is from June to September, the Indian work in Yale is practically closed, because salmon fishing takes everyone to the coast early in the summer and afterwards the Indians stop at settlements on the Lower Fraser for hop picking.… The “Services” …are led by the Interpreter. Instructions are always given by Miss Moody.”

The school journal also reveals that Moody travelled to Spuzzum and other First Nations communities to provide religious instruction, in the course of which she was called upon for nursing and medical care. For example, in 1899, “Miss Moody was taken to see a very feeble old man, whom she found doubled up with cramp…so Miss Moody, with the readiness of resource born of experience in the ‘Wild West,’ took off the stove lid, wrapped it in rags, and applied it to the sufferer; the heat brought almost instant relief.”[48]

Inevitably a modern reader finds suggestions of the ethnocentric values of colonial society imposed by the missionaries and teachers. In the school journal in 1900, Moody observed that:

It is not the fault of the Indians that they have not learnt better, but rather our fault, who have withheld that training from them to the need of which they are slowly becoming sensible…. So let us hope and pray that it may not be very long before a beginning is made and the untutored minds of our Western brethren may reap advantages which Eastern minds have enjoyed for so many centuries.[49]

Elsewhere, Moody betrays an internalized sexism reflecting her late Victorian upbringing and training as a missionary steeped in devout, if dogmatic, Christian beliefs. She wrote, for example, that “It is too sadly true that through woman sin first came into the world, but Christmas night reminds us how God allowed a woman then, and still allows women now, to do all they can to atone in some small measure for the misery brought by a woman on the whole human race.”[50] Of course, her Christian education and missionary worldview suited her to work in a school that aimed to assimilate First Nations girls into European settler culture.

The school at Yale took its toll on Moody. She was “invalided home” to England several times during her twenty years there. In 1899, for example, All Hallows in the West recorded that:

Dr. Neville Parker’s opinion, that Miss Moody required to be invalided home for at least six months complete rest, was received with great consternation by the family. We had all seen, for several months that her health was failing, but we hoped that the brief holiday she took in August would have proved of sufficient benefit to restore it… so we bowed to the inevitable, and sent our dear friend and fellow-worker off on her journey. [51]

Sometime early in the century, Althea Moody took her vows as an Anglican nun and appears thereafter in the school journal as “Sister Althea.”[52] She worked at All Hallows in the West until about 1911.[53] She then returned to the mother house at Ditchingham in Norfolk, founded “Little Sister of the Poor,” and was last heard of in India. On her death in 1930 she was buried in the All Hallows’ cemetery in Ditchingham.[54]

All Hallows School at Yale did not survive for long after Moody’s departure. School historian Sister Violet wrote that, by the second decade of the twentieth century, “applications for places fell off, and it became clear that the school should be closed. There was a school at Lytton, to which the Indian pupils could be transferred…. In 1916 thirty-three girls joined the boys at St George’s, Lytton. For two more years, the Canadian school carried on … until 1920 when the decision was taken to withdraw the Sisters back to the Mother House in England.”[55]

Uncovering Moody’s “hidden life” through her writing, watercolour journal, and other artwork reveals a devout woman dedicated to her school and religious order and talented and brave enough to leave a privileged life in England to work and live at an isolated mission school in British Columbia. We may never know if an internalized sexism, or the externalized sexism of nineteenth century western society, limited her from embarking on a larger role as a painter, but we are fortunate in what we have.

Her other legacy is as a colonial missionary. Although the work of All Hallows in the West was well-intentioned,[56] and despite Sh’Atjinkujin, her translation of the Communion Service of the Church of England, Moody and the other nuns and teachers followed a curriculum that led to First Nations students’ disassociation from their birth language and culture and adoption of nineteenth century Anglo-Canadian cultural values, practices, and language.[57] One can speculate that the hardship and difficulties of this work led to Moody’s frequent illness and took away the glow of the “bright continent.”

Among the holdings of All Hallows in Norfolk is an undated 8 x 10 watercolour of The Fraser River at Yale, an image that emphasizes the monumentality of the mountains and the quiet but relentless flow of the river. On the back of the painting someone has written, “Linky Mountain, Yale B.C. by Sister Althea CAH [Community of All Hallows]. Many children at All Hallows School have climbed up and put their names in a glass bottle at the summit.”

This painting indicates that Moody continued to explore the landscape of the Fraser Canyon over the years of her residence in Yale. Given time, further examples of her fine work will surely appear.[58] Moody’s little travel journal, and her few paintings now in private collections or at the Yale Museum, are small but significant contribution to Canada’s heritage of landscape painting inspired by this “bright continent” and the railway company that promoted its route through the Rocky Mountains and to the Pacific.

*

Educated at UBC and Columbia University, Jennifer Iredale worked as a curator at several provincial heritage properties, including Barkerville, Point Ellice House, and Carr House. In 2015, she retired as Director of the Heritage Branch for the Province of British Columbia, and in the same year the BC Museums Association gave her its Outstanding Achievement award. She has published on building conservation, exhibit curation, and women in colonial B.C. Her most recent article is “Eldorado Vernacular: Barkerville and its Buildings” in BC Studies 183 (Spring 2015). She lives in Victoria and on Mayne Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] Althea Moody, “Across the Bright Continent” (unpublished sketchbook, 1891), All Hallows Community Archives, Ditchingham, England. For another travel journal written by a woman and documenting an 1886 trip across Canada in the late nineteenth century, see Mrs. Arthur Spragge, From Ontario to the Pacific by the C.P.R. (Toronto: C. Blackett Robinson, 1887). All Hallows School has been the subject of considerable scholarship. See Jean Barman, “Lost Opportunity: All Hallows School for Indian and White Girls,” British Columbia Historical News 22: 2 (Spring 1989), 6–9; Jean Barman, “Separate and Unequal: Indian and White Girls at All Hallows School,1884–1920,” in Indian Education in Canada, ed. Jean Barman, Yvonne Herbert, and Don McCaskill (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1986); Andrea Laforet, and Annie York, Spuzzum: Fraser Canyon Histories, 1808-1939 (Vancouver: UBC Press and Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1998), 161–63; Jennifer Iredale, Enduring Threads: Ecclesiastical Textiles of St. John the Divine Church, Yale, British Columbia, Canada (Harrison Mills, BC: Fraser Heritage Society, 2004), 13–21.

[2] According to correspondence on file at the Historic Yale museum, “the tradition was that this was a ‘hidden life’ and talk about your achievements, your relatives, and life before you joined was discouraged.” Sister Violet to Rachel Edwards, 1 April 2002, on file at the Historic Yale Museum.

[3] Iredale, Enduring Threads, 16.

[4] In 1900, the All Hallows school magazine, All Hallows in the West, reported that “being no less than a cable from Mr. Moody, which informed us of the delightful and unexpected fact that the ‘New England Society’…had made a grant of £350 [nearly $1,700] to enlarge All Hallows Indian School at Yale! … Mr. Moody is one of the Trustees for the schools and we feel that it is largely owing to his kind efforts that this grant is obtained for us.” East and West (Michaelmas, 1900), 38.

[5] 1891 England census, RG11, Piece: 826, Folio 72, page 40, GSU roll 1341195. National Archives, London, England (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2005).

[6] From the online database, Cambridge University Alumni, 1261-1900 (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 1999). Original source, John Venn, ed., Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1922-1954).

[7] “Youngest daughter of loyalists Jane Hatch and Hon. Neville Parker” New Brunswick Courier, August 1, 1863, retrieved from Daniel F. Johnson’s Database of Vital Statistics from New Brunswick Papers (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick) http://archives.gnb.ca/Search/NewspaperVitalStats/Details.aspx?culture=en-CA&guid=a53a3ccf-0cc5-4f18-85b9-d575441d04cb&r=1&ni=208481

[8] Ibid

[9] For her date of birth see “A June Birthday,” All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas, 1904), 354. In the 1871 Census of Canada, six-year-old Althea is resident in Halifax Ward 2, Halifax West, Nova Scotia. According to Cambridge University Alumni, Harry Moody served as Secretary to the Governor of Nova Scotia between 1867 and 1873.

[10] Cambridge University Alumni and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; 1881 England Census, RG11, Piece 826, Folio 72: 40, GSU roll 1341195, National Archives, London, England (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2004).

[11] For her 1881 whereabouts, see 1881 England census, RG11, Piece: 2751, Folio 25, page 13, GSU roll 1341659, National Archives, London, England (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2004). Her school, St. Anne’s, was established in 1874 as the first Woodard School for Girls. Althea would have been taught by Alice Mary Coleridge, the Anglican Lady Warden of St Anne’s from 1878, who was known to have “instituted a Spartan regime and a broadly based curriculum.” Wikipedia, s.v. “Abbots Bromley School,” last modified November 5, 2015, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbots_Bromley_School

[12] Sister Amy of the Community of All Hallows travelled to England in 1891 to “endeavour to procure a settlement of the questions relating to the Indian School.” The Churchman’s Gazette, August 1891: 4, 843, and recruited Althea Moody, “the daughter of a prominent C.P.R. official in London:” The Churchman’s Gazette, 1891: 5

[13] All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas-tide, 1899).

[14] Harry Moody, All Hallows in the West (Christmastide, 1900), 63.

[15] For his dates with the CPR, see Cambridge University Alumni; for his work with Van Horne see Allan Pringle, William Cornelius Van Horne: Art Director, Canadian Pacific Railway, Journal of Canadian Art History 8:1 (1984): 62.

[16] According to Pringle, Van Horne “attempted to justify the C.P.R,’s substantial expenditures in the area of fine art patronage by claiming that the works of art served as part of the Company’s advertising campaign to promote immigration to the North West…. It would be more realistic to speculate that fine art patronage was principally aimed at serving the vanity and aesthetic tastes of the C.P.R. directors and their business associates. Exhibitions by C.P. R.-sponsored artists tended to promote the Company’s image as a ‘nation-builder’ and as a contributor to the development of Canadian cultural affairs.” Pringle,William Cornelius Van Horne, 52.

[17] Nineteenth century artists in the CPR’s Railway Pass Program included Frederic Bell‑Smith, William Brymner, Oliver B. Buell, John Arthur Fraser, Robert Gagen, John Hammond, Thomas Mower Martin, William McFarlane Notman, and Lucius O’Brien. See Roger Boulet and Terry Fenton, Vistas: Artists on the Canadian Pacific Railway (Calgary: Glenbow Museum, 2009). On the work of the CPR artists, see also Douglas Cole and Maria Tippett, From Desolation to Splendour: Changing Perceptions of the British Columbia Landscape (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Company, 1977).

[18] Pringle, William Cornelius Van Horne, 62.

[19] The works shown at the RCA exhibition in Montreal in the spring of 1887 inspired several artists to ask Van Horne for passes to travel to the mountains that summer. Being unfamiliar with these artists’ work, Van Horne turned for advice to O’Brien, who not only endorsed the requests of Thomas Mower Martin and Forshaw Day, but added that Marmaduke Matthews also wanted to travel west. F.M. Bell-Smith also asked for a pass. These artists, and O’Brien himself, headed to the mountains that summer courtesy of Van Horne’s pass program. See Boulet and Fenton, Vistas, 67.

[20] Passenger lists of the Vancouver arriving Quebec, Que. and Montreal, Que. on 1891-08-15. Library and Archives Canada, accessed Sept 14, 2015, http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/immigration-records/passenger-lists/passenger-lists-1865-1922/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=2981&

[21] Canadian Pacific Railway: A Time-Table, 19-20.

[22] “In Banff, several views were quickly identified by photographers and artists, some featuring the most prominent mountains the in area, Cascade Mountain and Mount Rundle…. There are views of the Bow Valley looking west… and views of the Vermillion Lakes with the view of Mount Rundle to the east were soon identified as notable. There are also various views of, and from, the Banff Springs Hotel….” Roger and Fenton, Vistas, 94.

[23] Emily Carr, faced with similar preoccupations, famously wrote that “There is something bigger than fact: the underlying spirit, all it stands for, the mood, the vastness, the wilderness, the Western breath of go-to-the-devil-if-you-don’t-like-it, the eternal big spaceness of it. Oh the West! I’m of it and I love it!” Emily Carr, Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2006), 24.

[24] Boulet and Fenton, Vistas, 96.

[25] Canadian Pacific Railway: A Time-Table, 25-6.

[26] East and West, 1886-1919 (Norwich: A.H. Goode & Co.), 201-202.

[27] Boulet and Fenton, Vistas, 113-124.

[28] Canadian Pacific Railway: A Time-Table, 30-31.

[29] Ibid., 31.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Joan Schwartz and Lilly Koltun, “A Visual Cliché: Five Views of Yale,” BC Studies 52 (Winter 1981–82): 113.

[32] Andrew Onderdonk’s residence, “Brookside,” was purchased and refashioned to accommodate All Hallows School, which officially opened in 1890. Schwartz and Koltun, “A Visual Cliché,” 124.

[33] “Yale in the Morning, B.C.” (also known as “Fraser Canyon”), oil on canvass, painted by William Brymner, 1886, private collection.

[34] Janet Braide, “William Brymner: The Artist in Retrospect” (Master’s thesis, Concordia University, 1979), 53. The image is reproduced in Boulet and Fenton, Vistas, 66.

[35] Schwartz and Koltun, “A Visual Cliché,” 113.

[36] Moody’s term alludes to the title of a CPR promotional publication: Canadian Pacific Railway Company, The Canadian Pacific: The New Highway to the Orient, Across the Mountains, Prairies and Rivers of Canada (Montreal: Canadian Pacific Railway, 1891).

[37] Schwartz and Koltun, “A Visual Cliché,” 128.

[38] Canadian Pacific Railway: A Time-Table, 31

[39] Althea Moody is listed as a teacher at All Hallow’s school in the B.C. directories for 1893 to 1895, 1899, 1900/1901, 1901 to 1904 and 1910. I owe this reference to Jean Barman.

[40] Sister Violet, All Hallows: Ditchingham: The Story of an East Anglican Community (Oxford: Becket Publications, 1983), 65.

[41] Mrs. C.S. Bompas to Miss Moody, in All Hallows in the West (Christmastide, 1901), 79.

[42] Church of England, Sh’Atjinkujin: Parts of the Communion Service of the Church of England, Privately Printed for the Use of the Lower Fraser Indians in the All Hallows Mission Chapel, Yale 1891 (London: Darling & Son, 1894).

[43] Church of England, Diocese of British Columbia, Monthly Report on the Diocese of British Columbia, ca. 1895.

[44] All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas-Tide, 1900), 41

[45] All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas-Tide, 1899), 26

[46] All Hallows in the West (Ascensiontide, 1900), 18.

[47] All Hallows in the West (Christmastide, 1900), 63. For Indigenous work patterns in nineteenth century British Columbia see John Lutz, Makúk: A New History of Aboriginal White Relations (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008).

[48] All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas-Tide, 1899), 29.

[49] All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas-Tide, 1900), 41-42.

[50]All Hallows in the West (Christmas-Tide, 1899) 45

[51]All Hallows in the West (Michaelmas-Tide, 1899), 47.

[52] Rose Moody to Miss Harris, 3 December 1910, “A Letter from India,” All Hallows in the West (1910).

[53] Sister Althea’s presence at the school in 1911 is noted in All Hallows in the West (Midsummer, 1911), 7.

[54] The MS headed “Reactions – Mrs. E. R. Bell, Ladner, B.C. to Sister Louisa’s letter to Mrs. M. Stuart, Hope, B.C.” in the holdings of the Anglican Archives, Vancouver, Box “All Hallow’s School, Yale”, file “All Hallows’ School, Yale, B.C.”, records that Sister Althea “returned to England, took the veil, founded ‘Little Sister of the Poor’, was last heard of in India, obit 1930. I owe this reference to Jean Barman.

[55] Sister Violet, All Hallows: Ditchingham, 42.

[56] For an appreciation of the legacy of missionaries and others who worked and advocated for Aboriginal people in Canada, see David Nock and Celia Haig-Brown, editors, With Good Intentions: Euro-Canadian and Aboriginal Relations in Colonial Canada (Vancouver, UBC Press, 2006).

[57] These losses are described in Barman, “Separate and Unequal.”

[58] For example, Barbara Bjerring, the daughter of Marjorie Armstrong, a student at All Hallows in the West between 1898 and 1907, owns three watercolours by one of the All Hallows nuns — most likely by Sister Moody because of their similarity to those in her travel diary. Barbara Bjerring, interview by Jennifer Iredale, 8 Jan. 2004, Historic Yale Museum.

Comments are closed.