#100 The hermit of Chemainus

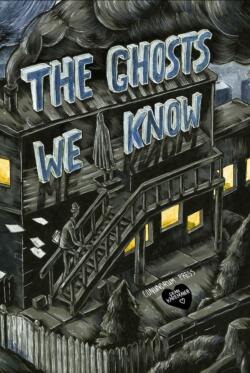

The Ghosts We Know

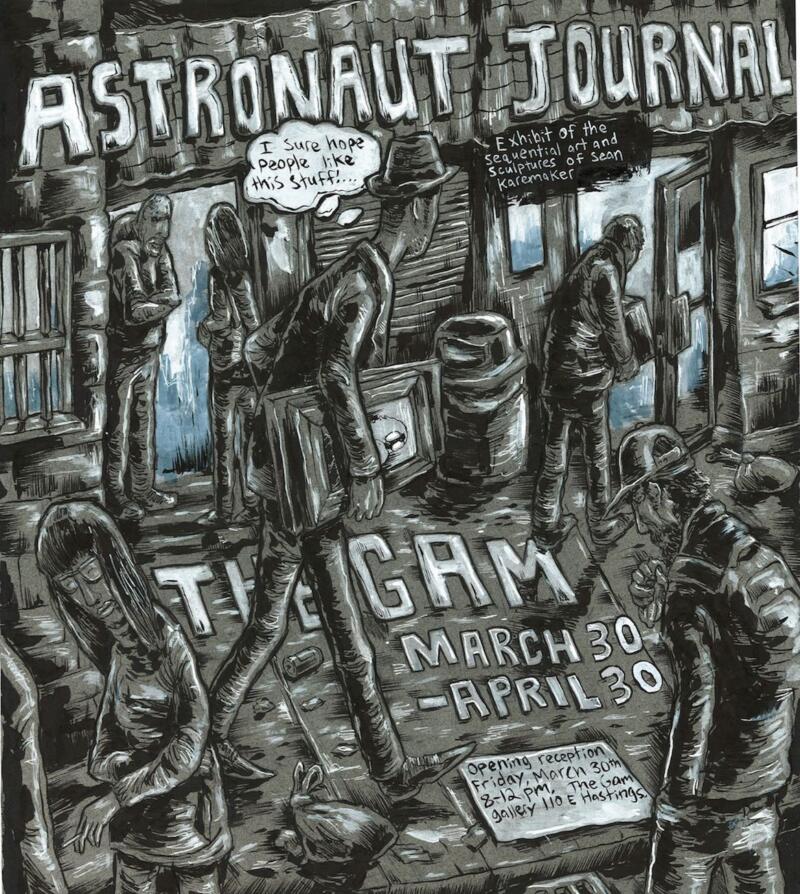

by Sean Karemaker

Wolfville, NS: Conundrum Press, 2016

$20.00 / 9781772620030

Reviewed by Michael Kluckner

First published March 7, 2017

*

In his first book, The Ghosts We Know, Sean Karemaker presents an artist’s recent journey through life on coastal B.C. from the quiet corners of rural Vancouver Island to the intense coffee shop culture of Vancouver.

In his first book, The Ghosts We Know, Sean Karemaker presents an artist’s recent journey through life on coastal B.C. from the quiet corners of rural Vancouver Island to the intense coffee shop culture of Vancouver.

Reviewer Michael Kluckner singles out Karemaker’s “fluid set of characters” and his “dim inner landscape” in this graphic novel. It includes old ghosts and free spirits who seem equally perplexed by a hermit’s shack in the woods, train and bus stations, urban cafés and talent shows.

“Most of the pages are drawn from a slightly elevated perspective,” Kluckner notes, “as if the artist were sitting atop a stepladder, eliminating any sense of horizon or sky but allowing the space to be populated by a fluid set of characters.” — Ed.

*

In a letter to his mistress in 1852, Gustave Flaubert wrote: “The author in his work should be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” Evidently he hadn’t reckoned on graphic novels, many of which are autobiographical narratives and imaginative memoirs.

Some of the most famous graphic novels — Maus, Persepolis, and Shigeru Mizuki’s Showa — feature the author as a major character. It is a medium that supports a confessional type of narrative, as in Sean Karemaker’s The Ghosts We Know, which reflects on his progress from boy to man all the time loving and drawing comic books.

Unlike the three titles mentioned above, Karemaker’s memoir doesn’t take place in the shadow of horrific or even dramatic world events.

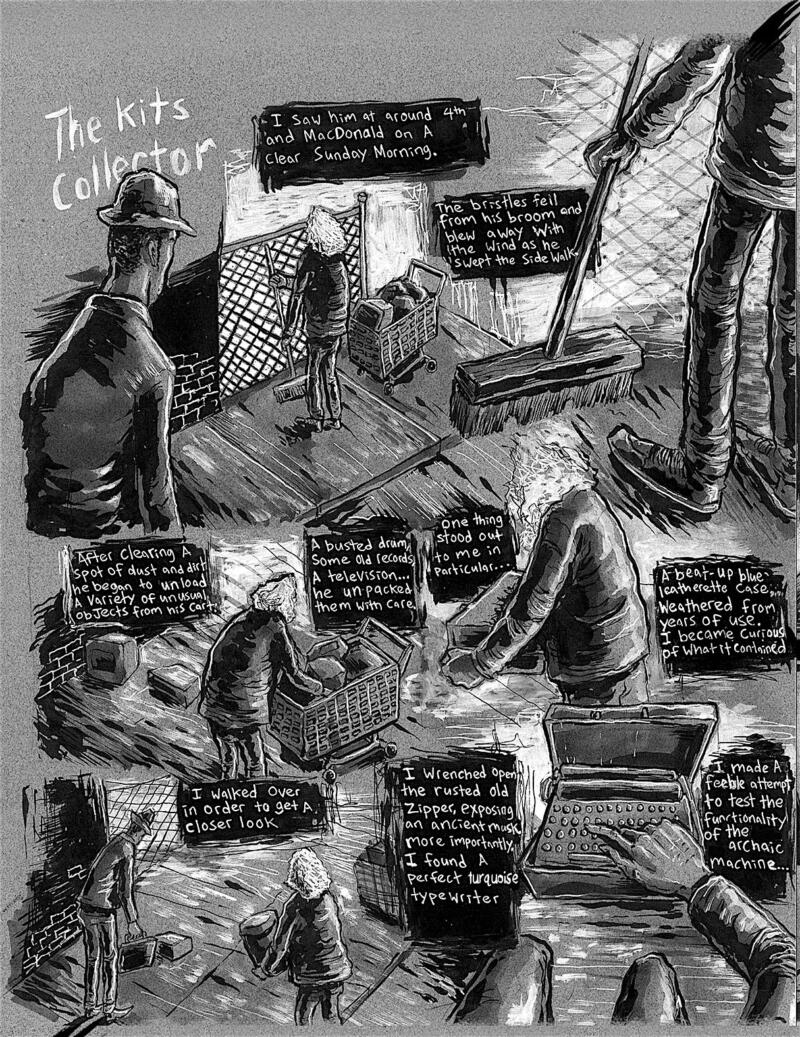

It is set largely on the east coast of Vancouver Island, in Chemainus and Crofton, with sections played out in Vancouver, including on the Skytrain and in Kitsilano, and there is an amusing reprise of the Kits Collector, a guy who sold and gave away scavenged things on the sidewalk in front of a gas station site at 4th and Macdonald.

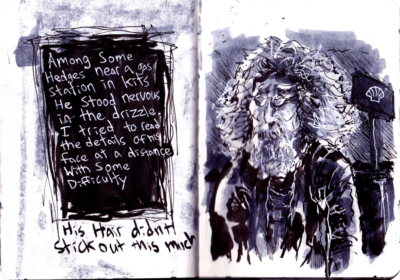

A recurring character is a hermit who lives in a trailer in the woods near Chemainus,

The author portrays himself as a nerd and a loser, and in a set of two-page, stand-alone chapters in the middle of the book he reflects on being bullied, about his failures at the team sports that are so much a part of a typical childhood, and his realization that his own success is his ability to draw and inspire others, such as in an art class he helps with in Chemainus.

Throughout the book, his memory is triggered by his surroundings, and he seeks to continue the comic-book stories he started as a boy. In some, he appears as an ungainly bird, such as at “God Camp” when he’s 10.

At the end, he returns to his childhood home and gets a box of his old comics — the ghosts of his childhood who form the community he imagines and draws. And, à la Thomas Wolfe, he realizes that you can’t go home again.

Karemaker dispenses with the ruled-off panels of most comics, preferring a kind of melded, double-page drawing that nevertheless, in most cases, reads from left to right and top to bottom.

Most of the pages are drawn from a slightly elevated perspective, as if the artist were sitting atop a stepladder, eliminating any sense of horizon or sky but allowing the space to be populated by a fluid set of characters.

The artwork is a kind of digital Scratchboard — with the exception of a 16-page colour signature, the backgrounds are grey or black and the people and objects are created mainly with pale digital patches and lines. It feels like a dim inner landscape, like a twilight, with dreams and visions pushing against reality. Dialogue balloons and narrative panels are hand-printed, some in black and some in white.

For my taste, the story relies too much on the little narrative panels rather than telling the story visually and with conversation between the characters. For example: “I would sit in a park at the edge of the water and watch the large shipping boats” adjoins a drawing of him sitting on a bench with boats going by.

I found the number of narrative panels made me skip over the artwork — I would have preferred to linger on it and discern the plot by analyzing it. And something about the B.C. geographer in me wanted to see an identifiable Vancouver Island, or even just Vancouver, landscape.

The book ends on an interesting premise, with the words “His work would inspire the man as he continued to grow,” followed by several wordless pages of a dreamscape with hospital beds scattered among the trees of a forest inhabited by ghostly aged strangers. Don’t throw out your old work, it seems to say. Your original thoughts are worth keeping.

*

Michael Kluckner is a writer and artist probably best known for his 1990 book Vanishing Vancouver and its 2012 sequel, Vanishing Vancouver: The Last 25 Years (both Whitecap Books). He was the founding president of Heritage Vancouver and chaired the Heritage Canada Foundation, and is currently the president of the Vancouver Historical Society. He has recently turned his creative attention to graphic novels, including Toshiko (Midtown Press, 2015), which dramatizes the Japanese-Canadian experience during the Second World War, and 2050 (Midtown, 2016), a murder mystery set in the ruins of a future Vancouver. He lives with his wife Christine Allen near Commercial Drive in Vancouver.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster