1650 Doukhobor affirmations

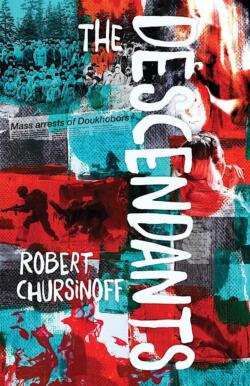

The Descendants

by Robert Chursinoff

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2022

$24.95 / 9780889714403

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

I very much enjoyed reading Robert Chursinoff’s first novel, The Descendants. I think it’s a remarkable achievement, one that deserves a wide range of readers, both for the appeal of the story it tells and for the importance of understanding the stories that have shaped it, stories of a BC history — of the group generally known as the Doukhobors — that has so often been misinterpreted and too easily set aside.

I very much enjoyed reading Robert Chursinoff’s first novel, The Descendants. I think it’s a remarkable achievement, one that deserves a wide range of readers, both for the appeal of the story it tells and for the importance of understanding the stories that have shaped it, stories of a BC history — of the group generally known as the Doukhobors — that has so often been misinterpreted and too easily set aside.

Caringly written, the novel is on the surface a straightforward love story — girl meets boy, girl and boy are torn apart by family, history, violence, flight, and desire, and then (spoiler alert) girl and boy find a way over time to get back together. But that’s too simplistic a description. In a more complex fashion, this is a carefully crafted book, about love: love as a belief, love as an action, and love as the force and life of an entire community. The way the narrative claims the future to be hopeful is just by itself a reason to appreciate this book, because it does so — espousing possibility in this fraught 21st century — even as it openly addresses the serious contemporary challenges of denial, distraction, and danger. So it’s not naïve, and hopefulness in the face of challenge possesses a particular kind of importance. But there is far — far — more to Chursinoff’s story than my reductive outline of the narrative structure suggests. Fastening mostly on the Slocan Valley (vividly recreated on the page), The Descendants acknowledges the checkered history of the Doukhobor community in BC; it faces the contemporary realities of war, drugs, prejudice, and popular culture; and it does not shy away from judging the biases of a society committed to tradition as well as the biases of those who give priority to material success. Chursinoff writes with insights born of experience and inquiry, and with extraordinary compassion.

The novel focusses on a handful of characters, and I’ll get to them shortly, but first it’s important to understand how the novel shapes its story. The narrative doesn’t begin with the events that disrupt the teenage lovers’ lives (that comes clear later on); it starts when the two of them (Ruby and Jonah) have chased off in different directions, one to an apparently successful but drug-addled musical career in California, the other to active duty in the American army in Iraq. (Yes, both are Canadian, and that, too, will become important.) Shaping these (fictional) actions is a series of real-life mini-histories (drawn through the established work of such writers as Woodcock, Avakumovic, and Svetlana Inikova) that trace the early history of the pacifist and anti-Czarist Doukhobor people in Russia (as early as 1692) who later (with the help of Tolstoy in 1902) emigrated to Canada; these mini-narratives also follow Doukhobor history in Canada, from settlement to prejudice to acceptance, exposing and explaining internal divisions along the way (especially between Traditional [pacifist, anti-materialist] and Freedomite [violent ‘ Sons of Freedom’ aka 1950s ‘terrorist’] groups). These mini-histories, which interrupt the fictional narrative, give important substance to the love story, for they recognize the cultural impact of divisiveness (expressed in one way through the arsonist actions in Krestova and elsewhere in the West Kootenays and in another way by the Canadian government when it set up a Doukhobor residential school in New Denver). This history of violence, both within and surrounding the pacifist group, is thus dramatically re-enacted in the early lives of the young couple. She (Ruby) comes from a Traditional family but seemingly rejects it to go on the [‘non-conformist’ American] road, and he (Jonah) has a suppressed Freedomite background that he must yet come to terms with. Divisiveness separates them. (This is more than a simple tautology.) Along the way Ruby will need treatment for her addictions, but will find strength in music; Jonah will have to deal with PTSD and the American war, finally discovering the value of ‘brotherhood’ while rejecting ‘meaningless’ slaughter.

The separate chapters that follow Ruby’s life in music and Jonah’s on the front (and the traumas they separately live through) are told with sharp, exacting detail. Each character finds friendship and loss, audience and dissatisfaction. And while apart, both are aware that any return to the Slocan Valley will find them in some way uncertain, in some way maimed, and just perhaps in some way also strengthened. IF. If they can deal with what has separated them. If they can come to terms with the violence in their lives (and the violence that has also disrupted the Doukhobor community and the pacifist traditions of the Doukhobor faith). Enter the parents, the quarrels that divide families (‘all happy families are alike; all unhappy families are unhappy in their own way’: Tolstoy’s maxim resonates), the challenges of reconciliation (think Doukhobor in and versus Canada as well within and between families), and the persistent nagging presence of the rivalry between the loving couple and a pair of brothers whose animosity seems antithetical to love and a barrier to closure. (There’s also a boy in the mix, whose presence has to be addressed, and several active members of an extended family, and some American friends, all of whom enter the story before a resolution can come about.) It’s a tall order, but the narrative carries it off animatedly, with a satisfying climax and serious reflection.

The problem brothers? The elder is drawn to weapons, attack, drunkenness, and biker gangs, and he faces opposition from the law and a rival gang. The younger is bitter and dependant and wheelchair-bound because of a series of violent events in which the two brothers and Ruby and Jonah as well have all been entangled. Which of them is responsible? (What is responsibility?) How will all four of them face up to their history? (What sort of justice will they face?) Which of them is ’free’? (Is violence ever acceptable?) How will civil justice interact with community values? (Or can it, will it?) I won’t sort out these tensions here: explaining too much in advance would deny the pleasure — the narrative satisfaction — of reading the novel through its episodes and into its denouement. Suffice it to say that Jonah (from the apostate family) and Ruby (the musician who doesn’t altogether give up music) will have something to say to each other and to the boy. And those brotherly American friends from the Fallujah battlefront? Some of them cross the border (a familiar but effective metaphor) and show up as ex-army/survivors/expats in the Kootenays, not far from a marijuana field and the site of congregational singing. This is more than a documentary narrative; it’s a fiction and a history combined — personal and socially pointed and seriously contemporary, passionate and compassionate and thoughtful. It’s at once a testament to the power of individuals to deal with their culture-crossed stories and a tribute to the tenets they choose to value. I look forward to Robert Chursinoff’s next book.

*

W.H. (William) New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. New’s most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (Rock’s Mills Press, 2021), reviewed by Gary Geddes. Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Harold Macy, Paul Sunga, Emily St. John Mandel, Tamas Dobozy, Rhonda Waterfall, and Leah Ranada for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1650 Doukhobor affirmations”

Thank you for your thoughtful review of Robert Chursinoff’s book, Bill. You hit on most of the points I would have done and did so sensitively. The Doukhobor story is sometimes difficult terrain. Being from the Kootenays I will promote it among friends there. Many of them will get a fresh look at the history in a contemporary setting. Ron Verzuh

Thank you for a most interesting review. I look forward to reading the book as I grew up in this culture in the 1940 and 50s in a traditional Doukhobor home. I remember the author’s grandfather Mr. Nick Chursinoff, and his father Freddie. I am certain that his grandfather would be very proud of his achievement!